The Medieval Iberian Peninsula enjoyed a Mediterranean climate, like many of the coastal lands such as Morocco, Algeria, Palestine, Syria, and Lebanon. It was in many ways similar to the irrigated lands farther east, in Iraq and Persia, on the same latitudes. Because of this, Spain too shared in the agricultural revolution of the Medieval period, which brought many new crops under intense cultivation. In fact, Al-Andalus was one of the centers of that agricultural revolution. Food and fiber crops such as rice, sugar cane, sweet oranges and hard wheat for bread and pasta were introduced into Spain from farther east, along with the migration of farmers and transfer of irrigation technologies.

Agriculture and gardening flourished in Muslim Al-Andalus, and its crops of oranges, almonds, and other fine foods enriched the tables and poetry of Europe. Oranges, lemons, and limes would not have become such a popular fruit in the west without the gardens of Spain. Figs were another important fruit brought to Spain by Muslims. The best ones were grown in Malaga, where they were exported as far as India and China. This was possible because figs, with their high sugar content, could be preserved by sun-drying and transported over a year’s journey. Sugar was produced and refined on a large scale, and played a part in the development of fine cuisine and fancy desserts, but also in the preservation of fruits before refrigeration. The taste for sugar entered Europe from Spain and from European contact during the Crusades.

Cotton was an essential non-food crop that made the textile industry possible, and its cultivation in Spain was also responsible for cotton’s spread to the New World. It would have been unthinkable to introduce these new crops without the intensive system of irrigation, water management, and agricultural technologies such as crop rotation, management of pests, and fertilizing crops by natural means. Spanish agricultural books describe these technologies and comprehensive knowledge about cultivation.

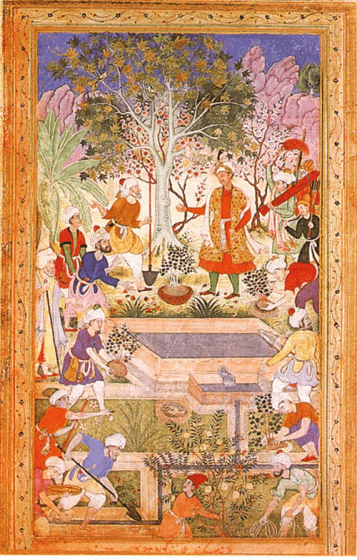

Ibn Bassal (fl. 1038-1075 CE) was an original scientist and engineer who lived in Toledo and wrote about agriculture. He described different types of soil and stated how often each should be plowed and irrigated to get the best yields. He described how to best engineer hydraulic systems made up of wells, ditches, and pumps. Other agricultural writers like ibn al-Awwam, and Abul Khair (early 1100s CE), al-Ishbili (late 1100s CE), and al-Tignari of Granada described sophisticated techniques such as grafting fruit trees, sugar-making, and preservation of fruits and vegetables. As a result, much new land was brought into cultivation under Muslim rule.

Irrigation systems were studied and policies were set down, determining exactly when each crop was irrigated, how stored reservoir and rainwater was used, and how water use by farmers and city dwellers was managed. As an example of how effective these systems were, the “Tribunal of the Waters” in Valencia is a group of officials that is still functioning from the time of Muslim rule until the present day, despite the fact that many other Islamic institutions were erased after the Reconquista and the expulsion of Muslims. This, however, was too vital a system to lose.

Lasting influences: Sugar cane, cotton and rice were key crops that the Spanish and Portuguese carried to the New World after the end of Muslim rule. In the New World, these crops were grown on a large scale in plantations using African slave labor. French, British and Dutch colonists gained great wealth from their possessions in the Caribbean. Without these cash crops, colonization of the New World by Europeans would not have been such an economic success. These global cash crops and several others that came to the attention of Europeans through trade and migration from Muslim lands were coffee, tea, bananas, and vegetables such as spinach and asparagus.

Flowers of many kinds that are common in gardens today also reached Spain during the heyday of Muslim rule, and their cultivation spread into Christian Spain and into other parts of Europe. The agricultural advances of the Scientific Revolution also owe much to the writings and practices in agriculture that passed into Europe through Islamic Spain and through their spread to the New World.