Chemistry is a theoretical and practical science, which is important to many technologies that rely on chemical reactions and useful compounds. Artisans and scientists contributed to theoretical and practical chemistry in Al-Andalus during the time of Muslim rule and after, through translation of books, discovery through experimentation, and by artisans of Al-Andalus, whose traditions were passed on to Spain and Portugal.

The science of chemistry is often described as growing out of a pseudo-science called alchemy. The word for both in Arabic is al-kimya. The goal of alchemy was to transform matter, and especially to make gold out of base metals, to find elixirs (in Arabic al-iksir) that could ensure long life, and even to try and create life. Even though later scientists dismissed these goals as unreachable or forbidden, alchemists learned a great deal about the natural elements by trying to reach these goals.

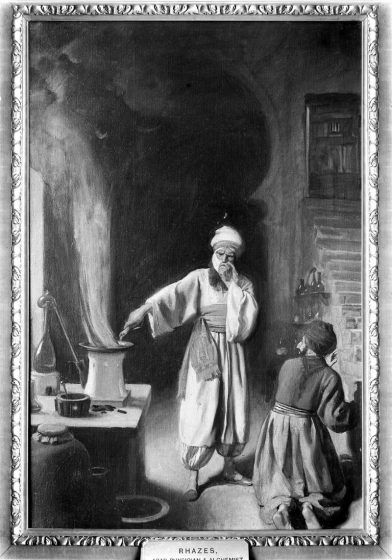

Alchemy and chemistry in the Muslim tradition built on classical and ancient foundations. The history of knowledge about chemistry runs on a scale from ordinary to mysterious. Al-Kindi distinguished investigation of substances from alchemy, an important step toward science. Physicians al-Razi (864-930 CE) and Ibn Sina (980-1037 CE) also wrote and investigated chemical properties and processes, discouraging alchemy, but encouraging scientific investigation.

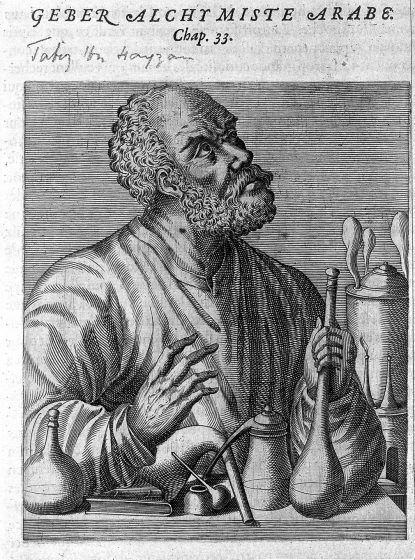

Jabir ibn Hayyan (died ca. 808 or 815 CE) was an alchemist, pharmacist, philosopher, astronomer, and physicist who is called “the father of Arab chemistry” for his important writings and discoveries. His works and techniques reached Al-Andalus, where they were translated into Latin under the name Geber. Jabir’s treatises on chemistry became standard texts in Europe. The Book of Chemistry, The Balances, and others were translated by Robert of Chester (ca. 1144 CE) and Gerard of Cremona (ca. 1187 CE) at Toledo. A 1545 CE printed edition of Geber calls it “… Arabic chemical knowledge made available to Latin reading people… the best Latin knowledge of chemistry.”

Among Jabir ibn Hayyan’s achievements were describing the process for making sulfuric acid, hydrochloric acid, and nitric acid (using saltpeter). He invented aqua regia, a substance that dissolves gold. This discovery was important for extracting, purifying and etching gold, but it was also key to alchemists’ efforts to transmute metals into gold. He isolated citric acid (what makes lemons sour), acetic acid (the acid in vinegar), and tartaric acid (from fermented grapes). Jabir’s work in chemistry resulted in improvements in metallurgy, dyeing and pigments in paints and textiles, waterproof fabrics, leather processing, and glassmaking. He discovered that adding manganese dioxide removed the green tint from glass to make it clear.

Jabir described how boiling wine released a flammable vapor, or spirit. Al-Razi is credited with identifying ethanol, or grain alcohol. The word alcohol in English derives from the name given to this substance by Muslim chemists. It was thought to come from al-kuhl, black antimony powder. A more logical derivation is the Arabic word al-ghawl, spirit, or intoxicant (Qur’an 37:47), source of the English word ghoul.

Jabir’s classification of elements into metals and non-metals laid the foundation for chemical naming systems today. He divided substances into three categories: “spirits” that turn to vapor when heated; “metals,” such as iron, copper, silver, gold, zinc, mercury, and lead; and “stones” or minerals that can be pounded into powdery form and used in many chemical reactions. Alkaline substances such as natron (sodium carbonate, or soda) and ash were widely used in manufacturing during that period in glassmaking, textiles, and soap. The Balances describes weights of substances based on a precise scale he designed and built which could accurately weigh amounts 6,480 times smaller than a kilogram.

Al-Majriti (d. 1007 CE) was a chemist from Madrid who built upon the work in chemistry done in eastern Muslim lands, and made his own achievements. His books, such as The Rank of the Wise and De Aluminibus, described his experiments in synthetic chemistry, and formulas for purifying precious metals. Al-Majriti was the first scientist to prove the principle of conservation of mass.

Practical applications of chemistry in Al-Andalus were found in all of the major industries. In mining, chemicals were used to purify and refine metals from ore by heating or mixing with other substances, and to process metal into products. Glassware and ceramic industries in Al-Andalus used sophisticated ovens and chemical substances to make glass and glazes from silica, adding metal oxides to make different colors. Minerals were made into acid and alkali compounds used in manufacturing. Vegetable and animal oils and even petroleum distillates (naptha: al-naft, for example) were used for lighting and solvents. Other artisans in Muslim lands used chemical processes for refining gems, making fixatives for textile and leather dyes, inks, paint, lacquer, and wood varnish.

Al-Andalus was a major center for processing flowers and herbs for medicines and cosmetics, using different chemical processes. Distillation (boiling and condensing) was one process described in Arabic books of chemistry, shown in the illustration. Others are subliming, crystallizing, dissolving substances in the right concentration, and preserving them in alcohol or syrup (both words from Arabic).

Hospitals and pharmacies in Al-Andalus used these skills and recorded them in manuals and books. Perfumes, essential oils, and cosmetics were made out of natural substances that are weak in their natural form, and must be extracted and concentrated. They also need to be attractive and pleasant to apply to the body. In the cities of Al-Andalus, perfumers’ shops were often located in streets near the main mosque.

Production of soap was widespread in Muslim lands during the Medieval period. Soap is made by mixing oil or fat with an alkaline substance (the Arabic word al-kali is the origin), made from ashes of certain plants. Emulsified, the mixture turns into solid soap. Castile soap from Spain became famous, and the Crusaders discovered soap-making centers in the eastern Mediterranean lands. Olive oil became the preferred type of oil for soap in Al-Andalus and around the Mediterranean. Castile soap is still sold in stores today.

Gunpowder is a compound made of potassium nitrate, charcoal powder, and other substances. It originated in China, where it was used for fireworks and early types of rockets. Muslim chemists experimented with this Chinese invention and wrote formulas for making gunpowder. The book Liber Ignium of Marcus Graecus, an early source of gunpowder formulas in Europe, was probably translated into Latin from an Arabic work found in Spain.

European scientist Roger Bacon published gunpowder recipes that some historians believe were derived from Arab chemists through these translations. There is evidence that gunpowder weapons and rockets were used by Muslim forces during the Crusades. Archaeological evidence of potassium nitrate has been found in Egypt from the 12th and 13th centuries CE. Syrian scholar Hassan Al-Rammah (d. 1295 CE) wrote a book on military technology that was translated into European languages. It explained how to purify potassium nitrate, and contained recipes for making gunpowder with the correct proportions to achieve an explosion. The first documented rocket is included in the book, of which a model is on exhibit at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington.

Both practical and theoretical knowledge of chemistry advanced in Muslim lands, and was transmitted to Al-Andalus, where it was further developed and transferred to those Europeans who built upon the collective knowledge of many cultures to create the science of chemistry as we know it today.