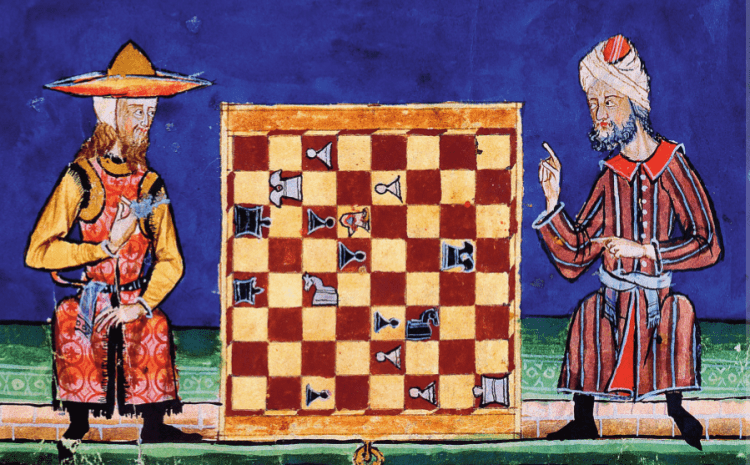

Much like video games today, Medieval board games were exercises of the mind that served not only as pastimes but as social occasions and serious mental training. Games require leisure time and reflect a luxurious and socially active environment. Al-Andalus was just such a place. In the courts and gardens of rulers and wealthy elites, and in the cities and marketplaces, people took time to play games. Rulers considered games of strategy like chess to be worthy activities for themselves, their courtiers, and their children’s training as thinkers.

Many literary sources such as poetry, biographies, and even scientific works prove that chess was played in Al-Andalus along with other games brought there from eastern Muslim lands.

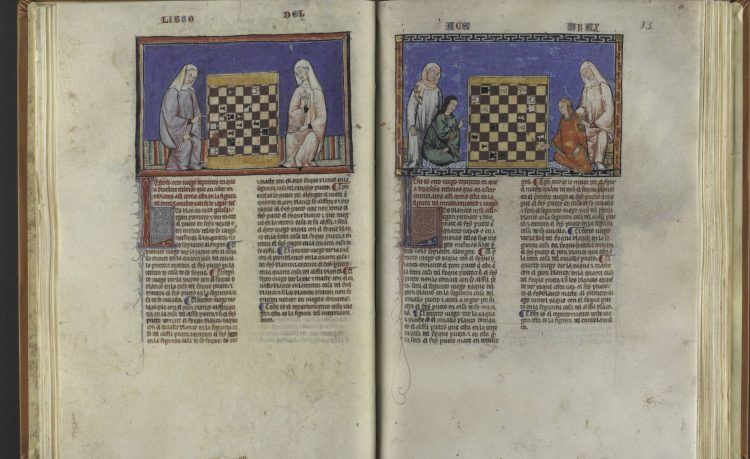

An important source of knowledge about games played in Al-Andalus is a 100-page illustrated book in Castilian called the Book of Games, or Libro de los Juegos, commissioned between 1251 and 1282 CE by the Christian ruler of Toledo after the conquest of the city from Muslims. Alfonso X, King of Leon and Castile, “Alfonso the Wise,” commissioned many translations of Arabic works into Latin, and his work documents the transfer of knowledge and culture from Al-Andalus to European or Western civilization. As he dictated the book to a scribe, he noted that God permits pastimes, and said:

…those who like to enjoy themselves … or those who have fallen into another’s power, either in prison, or slavery, or as seafarers, and in general all those who are looking for a pleasant pastime which will bring them comfort and dispel their boredom. For that reason, I, Don Alphonso … have commanded this book to be written.”

The book describes chess, the game that originated in India or even China, and became known in Persia as shatranj. Originally, the game was played with animal pieces — an elephant, a crocodile, a mythical bird (see left). Later the pieces came to represent the shah, or king, his minister (wazir), knights, and soldiers. In Europe, the game pieces came to reflect the feudal system. As the battle game moved westward, the wazir seems to have changed into a queen, and became a more important piece in the game. Scholars are not certain, but this change may have come about in Al-Andalus. The object of the game, which requires great patience, skill, and analytical effort, is to kill the king — al-shaykh maat in Arabic, or “checkmate.”

Chess entered Europe on more than one pathway. Harun al-Rashid (d. 809 CE) is said to have sent a diplomatic gift of a chess board and pieces to Charlemagne (d. 814 CE) — an ivory set that still exists — but some scholars think chess came to Europe around 1000 CE through Al-Andalus, and the set belongs to a later time.

Another game depicted in Alfonso’s book is backgammon, still played widely today in many countries. Al-Masudi (d. 956 CE) wrote about backgammon in his collection of anecdotes Meadows of Gold. It is a game of skill, but depends on luck as well. People enjoy the combination of luck and skill as a reflection of the tension between human fate and individual free will. Backgammon came to Al-Andalus with the transmission of other fashions and lifestyles.

The game shown below is called Morris — the mill game — in Spanish alquerque. Its board has lines that intersect, onto which players move pieces with a roll of dice. By strategy, the pieces move to form a line of three pieces on intersections or other variation, and eliminate the opponent’s pieces from the board. The origins of this game is said to be the Roman Empire, but there is evidence that it arrived from Asia, and was played in Al-Andalus.

Alfonso’s book contains many other games whose origins are not always certain, but surely reflect the mingling of many cultural groups from Africa, Asia and the Mediterranean region, and are unified by the enjoyment and togetherness that games bring to families, friends, and associates. They have been enjoyed in social circles among rich and poor, men, women, and children, like the early version of 3-in-a-row or tic-tac-toe from the Book of Games at right.