The rapid expansion of territory under Muslim rule fell in line with Qur’anic recommendations to encourage travel in search of knowledge and other benefits.

For example, one passage reads: “Have they not traveled in the land, and have they hearts wherewith to feel and ears wherewith to hear?” (Qur’an 22:46). Another passage states: “And of His signs is this: He sends herald winds to make you taste His mercy, and that the ships may sail at His command, and that you may seek His favor, and that you may be thankful” (Qur’an 30:46).

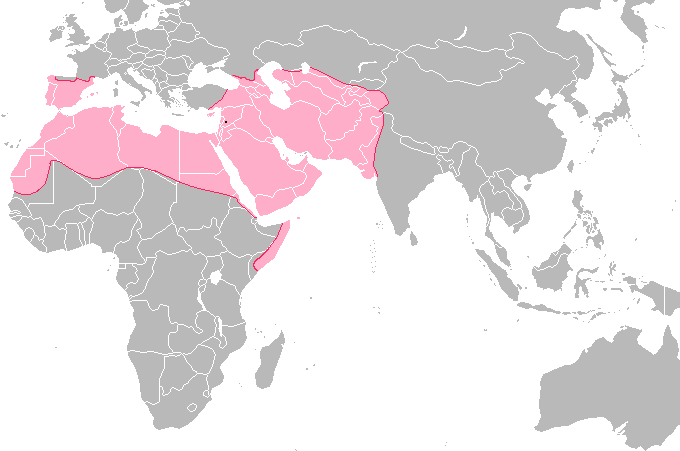

By the 8th century CE, Muslim lands stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the borders of China, and from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean. These lands included a variety of peoples, landscapes, climates, and customs. Among the earliest forms of scholarship were the accounts of travelers and diplomats describing the places where they traveled. A great collection of ideas and knowledge was the result. Among these travelers — which included scientists in mathematics, astronomy, and other fields — were those who compiled geographic works full of information about other places, people, and technologies.

Muslim geographers began their work on the basis of Greek and Roman traditions of geographic writing, especially Ptolemy’s Geographia. They soon overtook the limited knowledge of their predecessors, however, both because of the huge Muslim territory and expanding trade networks, and because of technical advances in mathematics and astronomy that allowed more accurate surveying on land and at sea. The earliest geographic works by Muslims are from the 9th and 10th centuries, and the work continued on into Ottoman times in the 16th century and beyond.

Among the earliest Muslim geographers were al-Khwarizmi, the mathematician, who participated in a project to draw a map of the known earth in the early 9th century CE. Al-Kindi, the philosopher, wrote an account of the inhabited parts of earth as known then. Some of the greatest traveler-geographers were Ibn Hawqal, who traveled for over 30 years and wrote about the places and people he saw, and the famous al-Mas’udi. He traveled, quoted geographic works that have disappeared, and wrote his own encyclopedia of geography and history called Meadows of Gold and Mines of Precious Stones in 956 CE. The Palestinian al-Maqdisi described the different climate zones, languages, towns, traded commodities, soils, and topography during the mid-10 century.

Many of these writers noted that the earth was round. Caliph al-Ma’mun sent a team headed by al-Faraghani to measure a degree of longitude in order to check the Greeks’ calculations and measure the circumference of the earth. Al-Biruni (972-1050 CE) wrote The Book of India, in which he described the sciences of Indian civilization, the topography of the sub-continent, and even made many geological observations, such as noticing that an ancient sea must have covered the Indus Valley at one time. He studied the seas, and believed there was a passageway through the southern oceans, and related the tides to the phases of the moon. Al-Biruni was a mathematical geographer who accurately plotted the Indian coastline by calculating the longitude and latitude coordinates of cities and ports.

The works of these geographers were available in important libraries of Muslim lands, including Spain. Though many have been lost, some of these works have been translated into European languages, and edited in printed Arabic editions for modern scholars. As proof that this geographic knowledge was available in Al-Andalus, the library at Seville still houses an atlas with Christopher Columbus’ handwritten notes in the margins, called Imago Mundi.

Among his notations was one that cited al-Faraghani’s calculation of a degree of longitude (56 miles @ 1 Arabic mile = 4000 “black” cubits). Measured by today’s understanding of a mile, the correct distance is 69 miles, but al-Faraghani was using a different standard for the cubit. His measurement was only off 2 miles, but Columbus understood it as the standard used in his time and place. Modern historians have sorted this misunderstanding out, but Columbus’ error at the time was one of the most famous mistakes in history.

Andalusian geographers studied the works brought to Córdoba and other Andalusian libraries from Baghdad. Working in the same tradition close to home, Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Razi (d. 955 CE) produced a geography and history of Al-Andalus, and Muhammad ibn Yusuf al-Warraq (904-973 CE) wrote a description of the topography of North Africa.

Another notable Andalusian geographer was Abu ‘Ubayd al-Bakri (1014-1094 CE) of Seville, who wrote the Book of Highways and of Kingdoms, and is well known for his early descriptions of West Africa. He wrote a geography of the Arabian Peninsula, listing villages, towns and places of interest to Muslim travelers. He created an encyclopedia of the world, including its known countries, their people, customs, history, and climate and listing their cities and landmarks, and relied on several earlier sources, including al-Tariqi (d. 973 CE) and al-Warraq.

The Andalusi Jewish merchant Ibrahim bin Ya’qub traveled to Germany and the Slavic countries during the time of Otto the Great and wrote about those places. The Granadan Abu Bakr al-Zuhri wrote the Book of Geography (jughrafiyah in Arabic) in which he relied on work done earlier at Baghdad. Another Granadan, al-Mazini (1080-1169 CE), traveled extensively in the eastern Muslim lands and wrote several important works, one of which is in the library at Madrid’s Historical Academy.

Travelers making the Hajj pilgrimage wrote some famous geographic works, including Ibn Jubayr (1145-1217 CE), who visited the Holy Land during the Crusades, and also wrote about Sicily after the Norman invasions, and visited Damascus, Cairo, and Baghdad. His work was used by many other Muslim writers, and exists in English today. Ibn Battuta (born 1304 CE) was a Moroccan, but he dictated the story of his decades-long, world-spanning travels to a writer while staying at the court of Granada. Ibn Battuta traveled for 28 years and related information about people, places, sea and caravan routes, cities, roads, and caravanserais. Ibn Sa’id al-Maghribi wrote a geographic work whose information ranged from West Africa to Mongolia, and included latitude and longitude coordinates that allow scholars to create maps from his work.

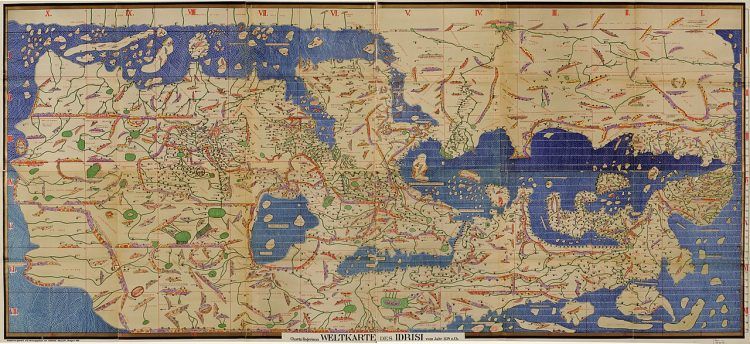

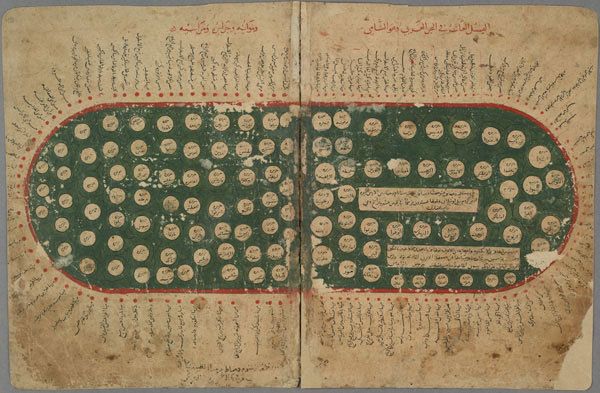

The most famous geographer of Al-Andalus was al-Idrisi, who studied at Córdoba. He traveled far and wide, and collected information for Roger II, Norman king of Sicily, who supported publication of a set of maps and information called the Book of Roger. The information contained in the Book of Roger was also engraved on a silver planisphere, a disc-shaped map that was one of the wonders of the age. Although al-Idrisi is famous for the round map of the world shown at right, he made over 70 maps that charted territories never before put onto a map. The lands around the Mediterranean are so accurately shaped that parts of them can be compared with satellite images. The al-Idrisi rectangular map at the beginning of this article is an example.