The Mediterranean region is one where water conservation is vital in summer. Rainfall is limited mainly to the winter, and summer crops need irrigation, while people and animals need water for drinking and bathing. Deserts meet the southern and eastern borders of the Mediterranean region, and because of this, water management technologies have spread to the better-watered areas of the Mediterranean from arid lands.

Hydraulic technologies in the region have reaped wonderful rewards: productive fields, beautiful gardens, sparkling fountains and populous cities. Many important food, fiber, and flower crops were introduced to the region because of careful water management. A few examples are rice, sugar, cotton, citrus, almond, peach, apricot, and fig, but also roses and other beautiful and fragrant flowers, medicinal herbs and spices. They all became part of Mediterranean and Medieval Andalusian life.

What technologies were used to collect, channel, redirect and conserve water in Medieval Andalus? Rainwater was collected from ceramic-tiled roofs through a system of gutters and pipes that moved the water to underground cisterns for storage. Water from the winter rains thus became available for summer gardens. Spain’s rivers, such as the Guadalquivir (Arabic: Wadi al-Kabir, or Great Valley), had a system of dams and flood control walls built by its Muslim rulers.

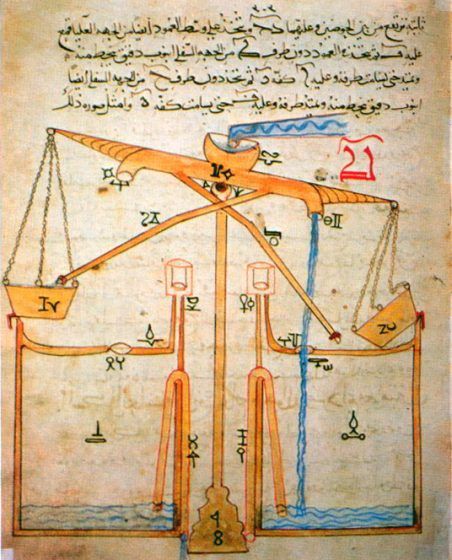

Aqueducts that had been built by the Romans were maintained and improved under Muslim rule to carry water from mountain streams to the cities and fields where it was needed. Some aqueducts let out into dancing fountains that worked without electric pumps (of course), by carefully harnessing the powers of gravity and water pressure using narrow pipes. Norias, or huge wooden waterwheels, were also carried over from Roman times and improved upon. Some norias are still functioning today. Their purpose was to raise the level of water from the source into the canal system, and maintain this level. Irrigation of farmland was carried out through a system of ditches and gates called in Spanish acequia (Arabic al-saqiyyah, “to quench”), which spread to the New World with the Spanish, and is still used in the American southwest.

Another important use of hydraulic technologies went far beyond farming or gardening, and beyond the beauty of sparkling fountains. Hydraulic technologies can be used to generate power — to harness the motion of water to do work. Today of course, hydroelectric power is generated as electricity. That innovation did not come until about a century ago. In Medieval times, water power was harnessed — literally like an animal — to push, pump, grind, pound, drill, and spin. The motion of water falling on a wheel fitted with paddles, or a river’s current pushing the paddles of the wheel, could provide a steady source of circular motion that could be transferred through a series of gears to turn a grinding wheel or a potter’s wheel. It could be changed into up-and-down motion with trip-hammers to pound wood pulp for paper, sugar cane stalks to extract the juice, or rice to break the hulls. This innovative use of the waterwheel in Andalus was transferred from eastern Muslim lands, from Persia, and even as far away as China. From Spain it spread to other parts of Europe. Another technology similar to hydraulic power is the windmill. This technology is believed to have come from Persia, and the windmill became a prominent symbol of life in Spain, and then in Holland.

Windmills were also used to pump water out of wells, or out of mines, to keep miners safe. Windmills could grind grain much as a waterwheel could, but a windmill did not require a river, making it especially suited to arid, windswept lands. Windmills and waterwheels were among the important technologies that spread from Andalus to other parts of Europe during the time of the translation efforts of the 11th century. One way to trace the origin of something is to find evidence in the culture of the country. Don Quixote’s famous attack on the imaginary giants, which were actually windmills, is one such piece of evidence. Another is poetry, as in this poem about a waterwheel originally written in Arabic:

How wonderful is the waterwheel! It spins around like a celestial sphere, yet there are no stars on it.

It was placed over the river by hands that decreed that it refresh others’ spirits as it, itself, grows tired.

It is like a free man, in chains, or like a prisoner marching freely.

Water rises and falls from the wheel as if it were a cloud that draws water from the sea and later pours it out.

The eyes fell in love with it, for it is a boon companion to the garden, a cupbearer who doesn’t drink.

~ Ibn al-Abbar (Valencia, d. 1260 CE)