Fine fabrics made of cotton, wool, linen, and silk were so commonly traded that they were almost a form of currency. Each country produced homespun, ordinary fabrics for clothing from available fibers — in Europe, often wool. Luxury textiles — especially those woven, printed, or embroidered in multiple colors were exactly the type of goods well suited for long-distance trade — light in weight, valuable, and much in demand.

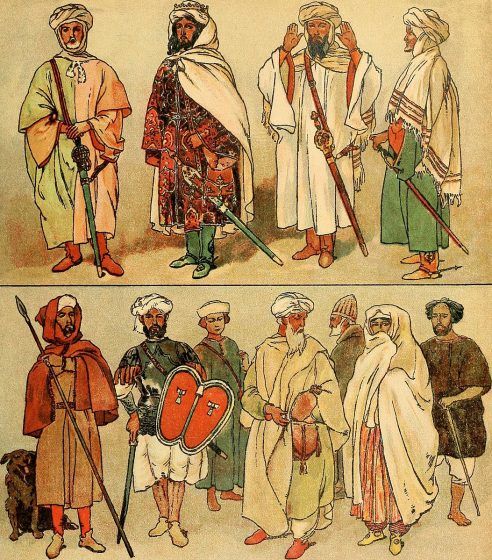

While the ordinary people wore drab colors and coarse materials, the wealthy ruling classes, both religious and political, indulged in “power dressing,” purchasing robes, vestments, and decorative fabrics that enhanced their authority.

Fine linens and woolens had been traded for centuries, and the volume of such trade increased during the Medieval period. The luxury fabric of choice, however, was silk brocade, in which different colored threads were woven into complex patterns. Ever since silk production arrived in western Asia from China, brocade weaving had been the technique of choice for luxury fabrics. Sassanian and Byzantine royal workshops produced brocades for palace, royal wardrobes, and religious institutions, as well as gifts of honor.

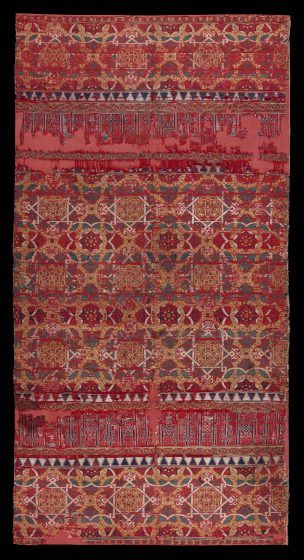

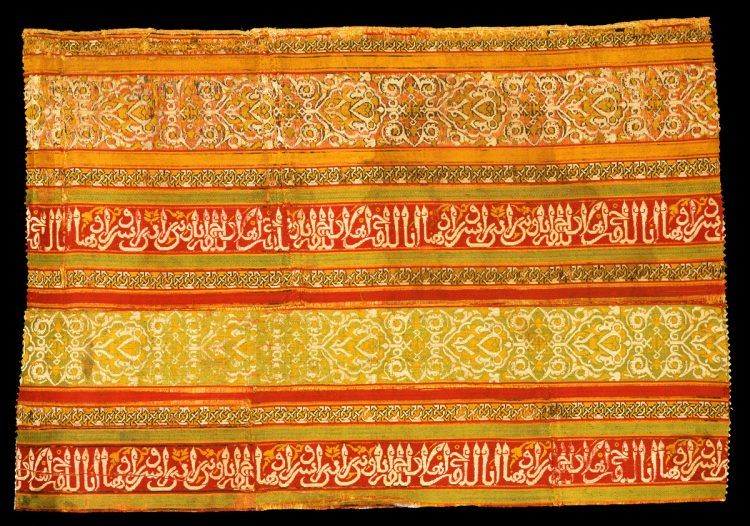

With the expansion of Muslim-ruled territory across western Asia and the Mediterranean, this tradition continued. The typical brocade motif of mythical and symbolic animals and geometric shapes was expanded to include geometric designs and Arabic inscriptions called tiraz. These banded inscriptions, woven or embroidered in colors and often with gold or silver threads, were highly prized for garments. Moving beyond the caliphal workshops, they became prized articles of trade.

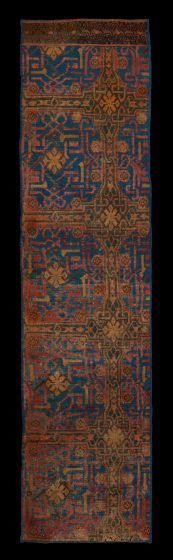

Al-Andalus became a center of silk production, including both import of silk thread and cultivation of silkworms. Styles and technologies from eastern Muslim lands kept pace with Andalusian fashions at the court and among the wealthy. Silk textiles became important articles of the export trade. Andalusian silks at first had similar design motifs like those of Persian, Byzantine, and Mesopotamian origin. Andalusian weavers also copied styles popular in Baghdad.

Brocade silks were one of those articles that crossed cultural and religious lines with ease. Brocades with Arabic inscriptions and eastern patterns are found as altar cloths, church vestments and even funeral shrouds in Christian possession. Muslims used them as wall coverings, robes, and over-garments, despite the prohibition against men wearing silks. People unable to afford the complete silk regalia employed woven bands on the edges of clothing or draped neck cloths (taylasan).

Among the silk designs were fanciful animals like griffins, lions, eagles, serpents, birds, and exotic plants of the east, arranged in symmetrical patterns, medallions, and alternating bands. The inscriptions sometimes attributed the qualities of these creatures to the wearer, or represented blessings and praises.

Córdoba was an early textile manufacturing center, where as many as 13,000 looms were active at one time. From the 10th century CE, it was producing silk fabrics, and in later centuries Almería also became an important export center.

The Almoravids developed textile production during the 12th century CE. Spanish weavers became especially skilled at weaving complex designs with fine lines between the colors, and very densely woven threads. The surviving examples of these textiles are still brilliant in color.

They appear in Church treasuries, and in early Renaissance Italy, they are carefully depicted in paintings, often with religious subjects. Almohad period silk textiles are simpler in design, reflecting their rejection of the animal motifs in favor of Islamically acceptable geometric motifs much like the tiles, bookbindings, woodcarvings, and architectural patterns of the time. Wealthy buyers in Christian territories highly prized these textiles, even with Arabic inscriptions. From Spain, Sicily, and Egypt, the techniques and styles of brocade weaving later spread into France and Italy, and then into northern Europe.

A famous example of an Almohad textile is the wall hanging known as the Las Navas de Tolosa Banner, dated between 1212 and 1250 CE, believed to be a battle trophy won by the Castilians. It has an elaborate geometric design with bands of Arabic inscriptions and Qur’anic quotations.

The rich agricultural land of Al-Andalus was able to meet demand for textiles with its domestic production in linen and wool. Both were grown there in Visigothic times, but production increased with the prosperity of farming under Muslim rule. Cotton was a new introduction to Al-Andalus from eastern Muslim lands. The crop was grown in irrigated areas. It was well suited to the need for cool, washable clothing in summer and for household fabrics.

Long-fibered cottons were an innovation in agriculture and textile production, being one of the important crops that moved across Muslim lands during the Medieval period. Cotton textiles were traded regularly between North Africa and Al-Andalus. Historians have found evidence that linen, wool, and cotton were also imported into Al-Andalus for weaving and dyeing for export, which speaks for the skill of Andalusian textile artisans.

In the later period of Muslim rule in Spain, Merino sheep, whose fine wool is still prized for textiles, were probably introduced from Morocco. Wool, linen and cotton were also combined to produce specialized fabrics that gave the textiles certain qualities, including combinations with silk thread.

Al-Andalus produced and exported fabric dyes that were an important aspect of high quality silks, linens, cottons, and woolens, giving them vibrant and lasting colors. Yellows were made from saffron — though it was very expensive, since it was extracted from the stamen of a crocus flower. Reds came from qirmiz (kermes), an insect that produced a brilliant red color from its body. Cochineal, a similar intense red produced by insects, was imported from the New World after 1500 CE.

Another red was produced by the madder plant, whose roots were crushed and processed, or red from brazilwood. Woad is a plant similar to indigo that was used throughout Europe for blue dye. It had to be crushed and fermented to release the blue color. This blue dye was colorfast when mixed with alum — a product of mining that fixed the color onto the cloth fibers. Alum was an essential export for Iberia and the Middle East in Medieval times, when Europe began to export textiles. Indigo was also imported into Spain for the textile industry from eastern Muslim lands. Andalusian agricultural books mention dye plants like safflower, saffron, wild madder and sumac.