Article: The Art of Islamic Spain

Written by Countess Patricia Christine Jellicoe

The Alhambra, site of the first presentation of the exhibition “Al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain,” has been an Orientalist fantasy since Washington Irving rediscovered it for the Western world in his delightful Tales of the Alhambra, written in 1832. But the 13th-century citadel and palace complex, set on a hilltop overlooking Granada, is not only the best known monument of the Muslim era in Spain, but itself one of that period’s greatest treasures. In this setting, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Administration of the Alhambra and Generalife together have produced a real and provocative new vision of almost 800 years of Islamic Spain.

Some 120 pieces of the finest Hispano-Islamic art from collections in America, Britain, Russia, Sicily, Egypt, Morocco, Spain and other countries went on display: ivory and marble carvings, bronze lamps and animals, coins, jewels and ceremonial swords, superb textiles, ceramics, astrolabes and the flowing calligraphy of Qur’ans, all restoring a vivid life to the rich, exotic beauty of the Alhambra’s interiors. The displays were a feat of installation: Nothing was permitted to touch the exquisite tiled and stuccoed walls, all cases and lighting standing discreetly free.

The exhibition catalogue presents the history of the various Muslim dynasties in Spain, from the first Arab conquests in 711 to the fall of the last Muslim kingdom in 1492 – for, in order to appreciate fully the art assembled in this exhibition, one should know something of the origins of Al-Andalus, of the powers and interests at play, of the widespread trade and travel of Spain’s Muslims and the resulting influences on their arts, and of the ebb and flow of hegemony in the peninsula, from the early days of Muslim-Christian-Jewish harmony and mutual tolerance to the final victory of the reconquista in Granada.

Some say the Arab conquest of the Iberian Peninsula began with an invitation: According to one account, the Umayyad governor of North Africa, Musa ibn Nusayr, was asked to aid the opponents of a Visigoth king. True or not, it is a fact that Ibn Nusayr sent his general Tariq ibn Ziyad with a Amazigh (Berber) army into Spain in 711, following himself in 712. Toledo lured Tariq to its conquest, and within seven years the whole of the peninsula, except for Galicia and Asturias, was under Muslim control, remaining so throughout the Umayyad period, from 711 to 1031.

The era of the Umayyad Governors was followed by the Umayyad Emirate, established in 756 after the arrival in Spain of ‘Abd al-Rahman I, sole survivor of the Umayyad caliphate of Damascus, which had been overthrown by the Abbasids in 750. The dynasty of the Andalusian Umayyads (756-1031) marked the zenith of Arab civilization in Spain.

But that dynasty collapsed after the death of the formidable dictator-chamberlain al-Mansur in 1002 and the civil war of 1010-1013, and local governors proclaimed themselves taifas, or petty monarchs, with Seville, Toledo and Saragossa the most powerful of the independent kingdoms. Their internecine wars cost territory: Muslim control had receded to only half of Spain by 1065. With the fall of Toledo to Christian armies in 1085, the taifas sought support from the North African Amazigh (Berber) Almoravid dynasty — but the Almoravid leader, Yusuf ibn Tashufin, believed that the rule of the taifas had to be ended if Islamic Spain was to be rescued. In 1090, Ibn Tashufin decided to land his army in Al-Andalus. One after another, Muslim-ruled cities fell to the Almoravids — Granada, Almeria, Seville, Valencia, Saragossa, Lisbon and the ‘Vest. Al-Andalus remained subject to the Almoravids until 1145, when they were replaced by the Almohads, another Amazigh (Berber) dynasty from North Africa’s southern Maghrib. The Almohad rulers adopted the title of caliph and introduced a series of religious measures seeking to strengthen their territories. Two great Almohad sovereigns — Yusuf I and his son Ya’qub – raised western Islam to the zenith of its power. But in 1212, at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, the Christian armies avenged their previous defeats, a turning point in the history of the peninsula. Only one-third of Spain was left under Muslim control and Al-Andalus was once again fragmented into tribute-paying principalities — Granada excepted.

The final dynasty, the Nasrid Kingdom (1238-1492), ruled only Granada and three tribute-paying cities: Jaén, Almería and Málaga. As pressure eased on Granada, the kingdom reached its greatest splendor during the reign of Muhammad V (1354-1359 and 1362-1391), when he added considerably to the Alhambra Palace. His ministers included some of the most learned men of the epoch: polymath historian Ibn al-Khatib, his close friend and fellow historian Ibn Khatima and court poet Ibn Zamraq. The royal court also extended its protection to Tunis-born Ibn Khaldun, the great philosopher of history. But by the end of the next century, the power of Christian Castile and Aragon, unified by the marriage of Ferdinand and Isabella — both pledged to the reconquista — forced the last ruling Nasrid, Muhammad XII, known to the Spaniards as King Boabdil, into exile on January 2,1492.

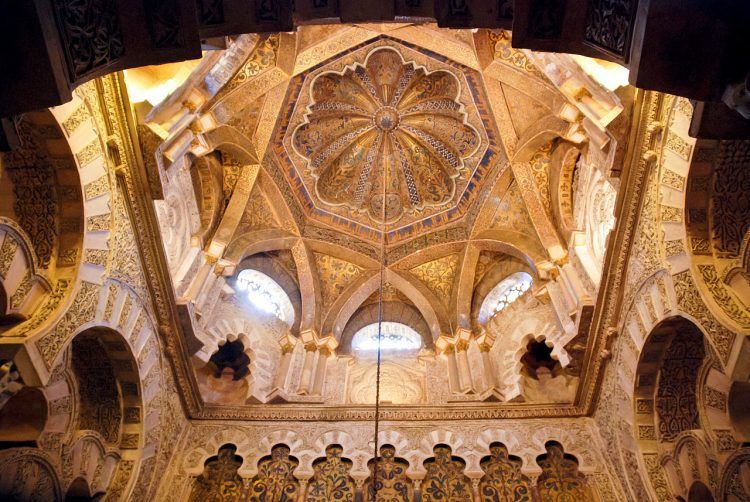

The city of Córdoba, whose Great Mosque still survives with its rhythmic arched vistas, became the center of a sophisticated, luxuriously rich Hispano-Islamic civilization that ranked with Byzantium and Baghdad. By the time of its apogee in the 10th century, Córdoba was renowned for its intellectually advanced culture, its learned centers and its libraries, far outstripping the still-undeveloped Christian north. In the late 11th century, Córdoba was incorporated into the Kingdom of Seville, where it remained, continuing to thrive as an intellectual center, until reconquered by the Christians in 1236.

In the exhibition, marble capitals from the Madi-nat al-Zahra Palace in Córdoba show the influence of Byzantine artisans invited to the court to train Muslims, while the schematized interweaving of marble window screens (celosías) is a forerunner of the later, geometrically more intricate Islamic designs. A supreme example of the quality of Umayyad artistic production is the deep overall carving of ivories such as the “Pamplona Casket,” dating from 1004 or 1005; with its foliated Kufic dedication to ‘Abd al-Malik and its images of princely hunting and feasting, traceable to textile patterns. Of 21 medallions on the casket, one outstanding one may show the reigning Caliph Hisham II — a bearded, bareheaded figure seated on a lion throne, a flower or fruit in his hand and a signet ring on his left ring finger. Flanking him are two attendants, one holding a fly whisk, the other a perfume bottle or sprinkler and a woven fan.

Two carved ivory pyxides — containers for precious aromatics — have the domed cover unique to 10th-century Spanish containers, and are designed to resemble a pavilion, with its palatial and paradisiacal connotations, suggesting the richness of the gifts within. One pyxis, made in 968, features within its overall carving large medallions of such vividness that they have been included in virtually all discussions of early Islamic art: One contains the ancient Middle Eastern motif of lions attacking other animals, bulls in this case; the second portrays a lute player on a lion throne, flanked by two seated youths; the third is of two beardless, bareheaded riders picking dates from either side of a tree while cheetahs seated on their horses’ flanks hold two parrots by the tail.

One of two 10th-century textile fragments on display, of silk, linen and gold thread, is thought to be part of an almaizar — a cloth which served as both veil and turban — of Hisham II, to whom there is a dedication in Kufic, while its embroidered medallions of people, lions, birds and other animals show Egyptian Coptic influence.

The Madinat al-Zahra Palace, built by ‘Abd al-Rahman III and his son al-Hakam II between the middle and end of the 10th century, was tragically looted and destroyed in the 11th century. Found in its ruins was the well-known bronze Córdoba Stag — probably made as a fountain-head – that is the surviving masterpiece of the palace’s metalwork atelier. The body of the stag has an overall pattern of leaves within circles, a common textile design of the period. Fountains were an integral part of Islam’s aesthetic — particularly in western Islam. Medical philosophies of the time maintained that health followed from the freshness of flowing water and perfumed air. The musk and ambergris from ivory pyxides, perfume from silver and gilt bottles, and perfumed candles would all have filled the palace’s rooms with scent.

The taifa kings emulated Córdoban power in their patronage of the arts; thus many scholars, merchants and the richest citizens emigrated to their realms, which became centers of small renaissances. Islamic literature in Spain attained its peak during the taifa era when the poet-king of Seville, al-Mu’tamid, established an academy of letters, and al-Mansur‘s poet, Ibn Darraj al-Qastalli, who took refuge in Saragossa, penned a series of qasa’id, or poems, of unequaled beauty.

In architecture, buildings took on new forms and decoration. An example in the exhibition from the Aljaferia in Saragossa, the best-preserved palace complex of the taifa era, is a carved-stucco relief with a design of interwoven arched columns — derived, perhaps, from the Córdoba Mosque’s curving maqsura arches, but giving birth to a new style of more complex and integrated geometrical shapes against a fuller scrolled-leaf ground. The relief still bears some of the red and blue color of the paints once used on all such stuccoes.

By the end of the 11th century, Al-Andalus was at the forefront of European sciences. The Saragossan king al-Mu’tamin (1080-1085), an outstanding mathematician himself, gathered at his court a distinguished group of scholars and philosophers. In the mid-11th century, Abu Qasim Sa’id ibn Ahmad of Toledo, in his book The Categories of Nations, discussed the schools of sciences which had developed since their establishment a century before by “the Euclid of Spain,” astronomer-mathematician Maslamah al-Majriti of Madrid — whose translated work was known to European monasteries. Muslims, Christians and Jews collaborated on the Materia Medica, a revision of the Eastern Arabic version of the first-century Greek physician Dioscorides’ text, while throughout Al-Andalus further medicinal plant properties were being discovered and disseminated.

The Andalusians excelled in astronomy, both theoretical and practical, perfecting their tables and the precision of their astronomical instruments. Trade and travel brought dependence on the celestial globe — known to Muslims from Ptolemy’s Almagest (See Aramco World, May-June 1992) — and the development of the Hellenic astrolabe, which became known to Europe through numerous Muslim treatises between the ninth and 16th centuries. Toledo astronomer Al-Zarqali, who died in 1087, simplified the astrolabe; his version, known as the saphea azarchelis, remained in use until the 16th century. He also anticipated 17th-century German astronomer Johannes Kepler by suggesting that the orbits of the planets are not circular but oval. Impressive elements of the exhibition are one of the two oldest known celestial globes, made in about 1085, and a Saragossan astrolabe dated with the hijri year 472 (AD 1079/80).

The true origins of the controversial 11th-century bronze “Pisa Griffin,” which once sat atop the cathedral in that Italian city, are unknown, but local legend calls it booty taken from conquest of the Balearic Islands east of Spain. Monumental and fearsome, the griffin stands rigid, its rounded chest and body, curled-back wings and beaked head covered in zones of textile-like feathering, scales and bands of Kufic lettering, with a tear-drop design on the legs portraying birds and animals in a scrolling surround, reminiscent of Sassanian Persia. But the puzzling meter-tall sculpture exhibits characteristics of many other regional styles as well, and it has been variously attributed to Fatimid Egypt, Fatimid North Africa, Spain, Sicily and Iran.

Silk textiles were a large part of Al-Andalus’s export trade, and the iconography of two 11th-century textiles is Middle Eastern — Sassanian Persian or Mesopotamian. Conserved in startling freshness is the lining of the Reliquary of San Mi-Han, in brilliant crimson silk with alternating friezes of confronting winged lions and paired griffins flanking the stylized “tree of life,” or hom, in green outlined in yellow. An altar panel, called “the Witches Pallium,” is an extraordinary design on crimson silk with a central frieze of half-sphinx, half-harpy composites of lions and eagles beneath arches of serpents with feline heads under attack by ibises; above and below are friezes of the hom between confronting peacocks.

The Almoravids vigorously developed textile production; the most prosperous and brilliant period was within the first quarter of the 12th century, with Almería taking over from Córdoba and becoming one of the first great manufacturing cities. The Almoravid silks that stand out above all others are often referred to as “the Baghdad group,” but should more accurately be termed “the Baghdad imitations.” Contemporary chroniclers call them “tabby” after al-‘Attabiyah, a district of Baghdad where such weaving was done.

A special technique in these textiles “favored fine woven lines between two juxtaposed colors and accentuated outlines in preference to massed color — a technique Spanish weavers developed with such skill that their delicate and intricate textiles are more like a painted miniature,” according to the catalogue. Their decorative style is based on large rondels, pearl-banded surrounds, and pairsof animals, face-to-face or back-to-back — lions, griffins, sphinxes, harpies, heraldic eagles, peacocks and others – Sassanian themes widely used since ancient times.

The best example is a 12th-century fragment showing “the Lion Strangler,” an ancient Middle Eastern motif: A man stands in turban and richly embroidered tunic between two confronting lions, which he strangles in the crooks of his arms; his head, hands, feet and belt and the lions’ heads are brocaded in gold in a unique system which joins the strands of oropel — tinsel, in this case thin threads of gilded leather — to produce a brocade with an unusual honeycomb effect.

These textiles were equally prized by Spanish Catholics: This particular fragment is from San Bernardo Calvo’s dalmatic, or religious robe. Another fine example is a 12th-century silk chasuble, badly worn but very beautiful, from the Basilica of Saint-Sernin in Toulouse. The vestment’s rondel design is formed by the spread tails of paired, facing peacocks with a stylized hom between them. There are also gazelles and dogs within each roundel, all standing on a pedestal on which Kufic lettering repeats the Arabic phrase “perfect blessing.”

Examples of textiles from the Almohad period are few, but of high quality. Simplicity and piety were enjoined upon them by their more austere religious beliefs, so the Almohad rulers initially had no royal textile and embroidery workshops, and prohibitions were issued against wearing luxurious silks. However, like the Almoravids, they finally succumbed to the attraction of rich textiles and resumed their production. Rondels containing animals gradually disappeared and circles were substituted with rosettes, lozenges, polygons and stars inspired by caliphal marbles, together with bands of script. Christians made use of such textiles as well, associating the fabrics with power and wealth, just as the caliphal rulers had.

Maria de Almenar’s coffin cover, dating from about 1200, is of great technical simplicity and magnificent artistry, with gold rampant lions and gold Kufic writing on a blue band against the crimson silk ground. The covered headrest for Leonor of Castile’s corpse, with its soft blue-and-gold bands, is totally Islamic in design: The central piece consists of silk and gold thread in overall geometric patterns, and a band of blue cursive Arabic script reads “happiness and prosperity.”

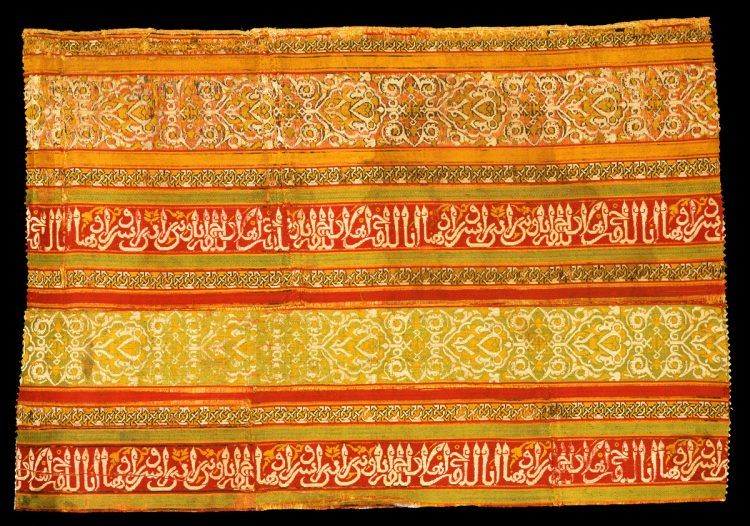

An important, carefully restored historical textile, dated between 1212 and 1250 and a tour de force in the Almohad tradition, is the striking wall hanging known as the Las Navas de Tolosa Banner, now held to be a trophy won by the Castilians in some other battle. Its central eight-pointed star is enclosed in a ring and a square of stars and circles, surmounted and edged with bands of large Kufic inscriptions and Qur’anic quotations.

The Almoravid and Almohad dynasties, both born of religious movements, introduced Qur’ans on vellum, parchment and paper – the oldest surviving one, dated 1090, lent to the exhibition from Uppsala, Sweden. From Marrakesh, a superb page from a 13th-century, 20-volume Qur’an is written in beautiful, large Maghribi script in brown ink, the sura (chapter) heading in Western Kufic and marginals in blue and gold on peach-colored paper, probably from Jativa, a center for Spain’s famed papermaking industry.

Morocco played a significant role in the history of bookbinding and influenced the craft’s later development in Europe, where the first gilded bindings did not appear until the mid-15th century. An engraved, gilded and painted Qur’an binding from Rabat (1178) has its distinctive flap, or lisan, intact (See Aramco World, March-April 1987). An exquisite, small blue-and-gold frontispiece, dated 1143, from a Córdoban Qur’an manuscript on loan from Istanbul, is a fascinating example of the mystic element in Islamic geometrical design, creating a sense of movement outward at the same time, paradoxically, as inward. Also from Istanbul comes a folio from a Qur’an copied in Marrakesh early in the 13th century — part of the sura titled Man/am, or “Mary.” The red-and-gold heading is written in Western Kufic script, with verses separated by gold and red-and-gold decorations. From the Vatican Library, the exhibition features one of the very few illustrated manuscripts to have survived from Islamic Spain, a version of the peerless love story of Bayad and Riyad.

Two immense mosque lamps, a generous loan from the Qarawiyin Mosque in Fez, document Muslim-Christian wars. Constructed around Spanish church bells taken as booty, 130 of these lamps once lit the Qarawiyin Mosque; now only 10 remain. The two lent to the exhibition are made of copper alloy; one is from the late 12th or early 13th century and the other from the North African Marinid era of the 14th century.

From the Nasrid period (1238-1492), along with a spectacular display of ceremonial arms and armor, comes the large, gold-lustered Alhambra Vase from the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, an early 14th-century storage jar of a kind first mentioned by Washington Irving. Part of a glazed mosaic tile dado, or pedestal element, from the Mexuar (council chamber) of the Alhambra “bears an interlaced design forming alternating stars of eight and 16 points” and half-stars of 10 points in a design of black, buff, green, and blue motifs on a white ground, the catalogue notes. Along the top of the panel is a script frieze repeating “Power is God’s, glory is God’s, dominion is God’s.”

Wooden ceilings, which have a long tradition in Hispano-Islamic Spain, attained their greatest splendor under the Nasrids. One of the most exquisite examples of workmanship and geometric design can be seen in the Alhambra’s own Salon de Comares, its beauty accentuated by the Metropolitan Museum’s lighting arrangements. The original cupola ceiling of the Partal Palace’s Torre de Las Damas shows an inventive transformation from a square to an octagon and from an octagon to a 16-sided figure, culminating at the crown of the roof in a 16-pointed interlaced star, with stalactites, or muqarnas, forming a cupola within the octagon.

Marquetry, or taracea inlay work, was used for decoration throughout the period of Islamic Spain, from the minbars of Córdoba’s Great Mosque and the Qarawiyin Mosque in Fez, to that of the Kutubiyyah in Marrakesh. The superb cabinet doors from the Palacio de los Infantes in Granada have their entire surfaces, inside and out, inlaid with silver, precious woods and green- and natural-colored bone in an intricate design of stars and wheels framed by hexagons, all within rectangular double guilloches, or twisted bands. A dazzling constellation in silver, they are a final accolade to the astonishing art of Islamic Spain.

Patricia, Countess Jellicoe is a London-based writer and lecturer on Middle and Far Eastern art and garden history. Born in China. She has lived in Beirut, Washington, Brussels and Baghdad.

This article appeared on pages 24-31 of the September/October 1992 print edition of Saudi Aramco World.