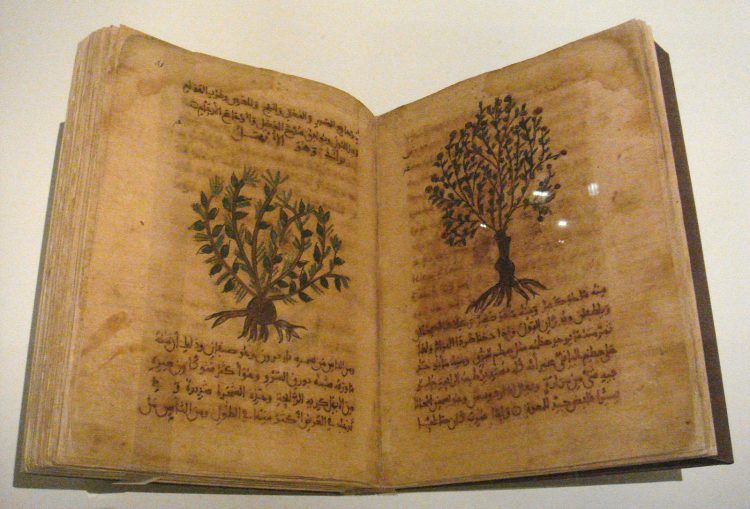

With the growth of Muslim territory and civilization, knowledge of medicine, which had accumulated in the classical civilizations over time, became available to those living in Muslim lands. With the spread of Arabic language and the effort to translate important works from other languages of learning, this heritage was concentrated in the Muslim libraries. Knowledge of diseases and diagnoses, and ways of curing them with medicines, surgery, and other treatments were published, along with advice on staying healthy.

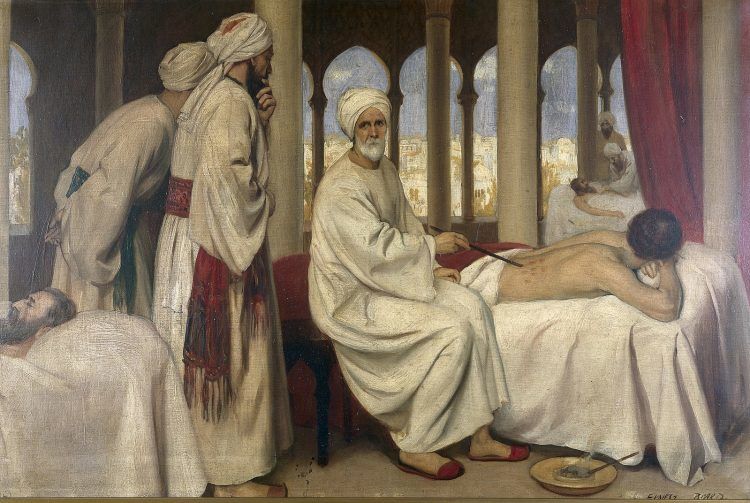

In Muslim cities, hospitals were founded and became centers of learning — the teaching hospitals of today. Rulers and wealthy people consulted physicians to help them overcome diseases, and supported their work in advancing medical studies.

Among the sciences that flourished in Muslim civilization, medicine is one that perhaps most represented a multi-religious, multi-ethnic effort. The number of physicians of different religions working in the institutions of learning and serving as court physicians includes Jewish, Christian, and Indian physicians and researchers. This is true in the eastern Muslim lands as well as the western.

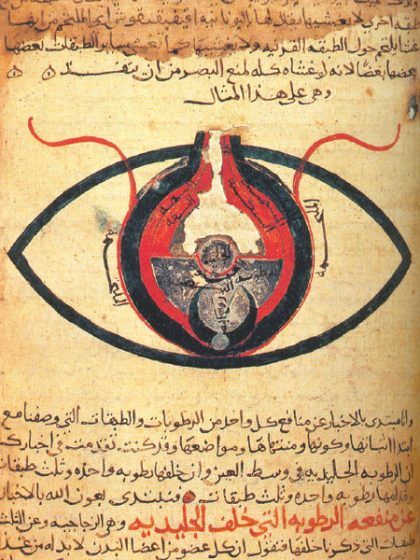

For example, the first head of the House of Wisdom in the 8th century, and a physician who contributed knowledge about the anatomy of the eye, was al-Hunayn, a Nestorian Christian mathematician and physician. His co-religionists, the Bakhtishu family, served the Abbasid in Baghdad court as physicians for generations.

Translations of Greek, Indian, and Persian medical works were available in Al-Andalus. Medicinal substances were imported through trade networks across Africa, Asia, and Europe. New medical knowledge accumulated through practice and research in hospitals and medical colleges.

A famous Andalusian physician was Hasdai Ibn Shaprut (915-970 CE), a Jewish physician who served Abdul Rahman III (912-961 CE) at Córdoba, and translated an important work on pharmacy, using his knowledge of Arabic, Hebrew and Latin.

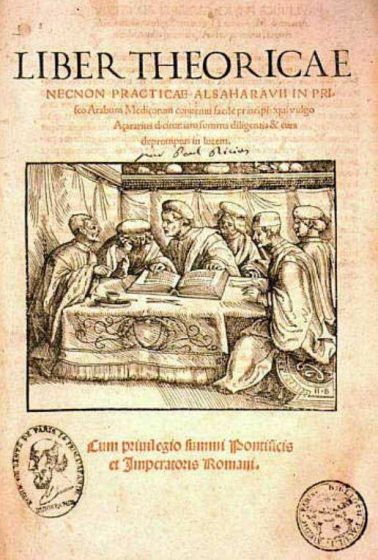

Famous Muslim physicians in Al-Andalus were many. Ibn Juljul (Córdoba, b. 943 CE) wrote a commentary on Dioscorides’ work of pharmacology De Materia Medica, and wrote Categories of Physicians, a history of medicine from the Greeks to his time. Abul Qasim al-Zahrawi (Córdoba, d. 1013 CE) is best known as a surgeon, and served al-Hakam II as court physician. Al-Zahrawi wrote about other diseases and treatments in his Tasrif — a leading medical text in European universities after its translation into Latin in Toledo, in which al-Zahrawi is called Albucacis.

Physician Ibn Zuhr (d. 1162 CE in Seville), known as Avenzoar in Latin, was the first to describe pericardial abscesses (of the heart) and to recommend tracheotomy when necessary. Ibn Zuhr’s Taysir was a standard medical work in Europe, translated into Latin in 1280 CE. In addition to his work in philosophy, Ibn Rushd (Córdoba, b. 1126) was both an accomplished physician and an astronomer. His famous medical book, Kitab al-Kulyat fi al-Tibb (known as the Colliget in Latin) discussed various diagnoses and cures for diseases, as well as their prevention. He was the personal physician to several Almoravid caliphs in Spain and Morocco. His friend Ibn Tufayl (d. 1186 CE) had been physician and medical author before him.

The great Andalusian physician Ibn al-Khatib of 14th century Granada wrote an important book during the time of the Black Death. On the theory of contagious diseases, he wrote, “The fact of infection becomes clear to the investigator, whereas he who is not in contact remains safe.” He described how transmission happens through clothing, vessels, and earrings, at a time when nothing was known about viruses and bacteria.

Andalusian doctors made contributions to medical ethics and hygiene. The jurist and philosopher Ibn Hazm wrote about the qualities that a physician should have: kindness, understanding, friendliness, dignity, and the ability to accept criticism. He wrote about the clothing and hygiene necessary for doctors. This cleanliness carried over into the hospitals, which had running water, gardens, and different wards for different diseases. The poor were treated there for free, and hospitals were open to all, supported by the government and private charities. They were also important institutions for training doctors.

Lasting impact: European medicine benefited from the knowledge and experience of Muslim and Jewish physicians in Spain and Sicily in many ways. Muslim medical science contributed knowledge of sedatives, the use of antiseptics to clean wounds, and use of sutures made of gut and silk thread to close wounds. Techniques for curing disease with drugs, for assisting childbirth, setting bones and curing eye and skin diseases, as well as knowledge of contagious diseases, were just a few contributions.

Visiting scholars in Islamic Spain were also exposed to the practice of medicine there, which was far advanced over that in other parts of Europe. The first European colleges of medicine developed at Palermo, Sicily, and at Salerno, Italy. During the 11th century CE, medical books by important Muslim physicians like Ibn Sina (980-1037 CE) and al-Razi (864-930 CE) were translated into Latin and brought into European universities, where they were used for centuries.

With the invention of the printing press in Europe, these books became widespread. The famous English writer Chaucer shows how well known this medical knowledge from the Arabs was in Europe. In the beginning of the Canterbury Tales, Chaucer names physicians from the Medieval Islamic tradition: Ibn Sarabiyun or Serapion as he was known to Europe, a 9th century Syrian physician; “Razis” the great 10th century al-Razi; and “Avicen,” or Avicenna (Ibn Sina), whose early 11th-century medical encyclopedia was a basic work for physicians. Arabic medical literature gave rise to European medical advancements.