The contest of Muslim and Christian Spain played out over nine centuries. While individuals and communities sought ways to thrive and cooperate in day-to-day life, larger forces were always at work.

Conflict took the more mundane form of battles fought for material gain and prestige. And, as often as Muslim and Christian leaders fought against each other, they fought against rivals who were their co-religionists.

For much of Medieval Spain’s history, leaders also were more concerned with maintaining economic and military power — just as other rulers worldwide — than on the rhetoric of crusade and jihad.

The following key battles involving Muslim and Christian forces in Al-Andalus reveal the complexity of military affairs. Each encounter represents a unique moment in the history of Al-Andalus, leading ultimately to its demise.

The Battles

Battle of Guadalete — July 19, 711

This battle took place close to the Guadalete River near the southern coast of the Iberian peninsula, between Muslim and Visigothic forces. An Arab and Amazigh (Berber) Muslim army of 7,000-10,000 soldiers crossed to Spain — “the land of the Vandals” or Andalus as they called it — from North Africa. The Amazighs (Berbers) possibly received the help of the governor of Ceuta, Count Julian. He confirmed that the peninsula offered numerous riches. The forces landed near a large mountain. It was later named Gibraltar (jabal Tariq, or Tariq’s mountain) in homage to the army commander, Tariq ibn Ziyad.

According to one account, Tariq burned the ships used for the crossing and stirred his troops with the words: “O People! There is nowhere to run away! The sea is behind you, and the enemy is before you. I swear to God, you have only sincerity and patience.”

Roderic was a Visigothic nobleman recently chosen as king. He had been fighting Basques in the north. Upon hearing of the new threat in the south, he rushed to meet the Muslims. His army is said to have been nearly 10 times larger than the Muslim forces. However, exhaustion from the long march and treachery on the part of other Visigothic rivals led to Roderic’s defeat.

With the routing of the Visigothic army — including many prominent nobles — the Muslim forces continued northward unhindered. They established garrisons in major cities and conquered many regions. Within a few years, virtually the entire peninsula came under Muslim rule.

The Visigothic kingdom came to an abrupt end. However, a local Asturian strong man named Pelayo fled to the extreme north beyond the reach of Muslim armies. There, he founded the Kingdom of Asturias. In subsequent centuries, Asturias was regarded as the origin point for the Reconquista.

Battle of Covadonga — Summer of 722

Seven years after the Muslim conquest of Iberia, a local Asturian strong man named Pelayo fled to the extreme north of the peninsula. There, he established the Kingdom of Asturias.

The Umayyad rulers based in Córdoba were unable to extend their power into Frankish territory. So, they decided to consolidate their power in Iberia. Meanwhile, Muslim forces made periodic incursions into Asturias.

In the late summer of 722, a Muslim army overran much of Pelayo’s territory, forcing him to retreat deep into the mountains. Pelayo and 300 men retired into a narrow valley at Covadonga. There, they could defend against a broad frontal attack. Pelayo’s forces routed the Muslim army, inspiring local villagers to take up arms, as well. Despite further attempts, the Muslims were unable to conquer Pelayo’s mountainous stronghold. Pelayo’s victory at Covadonga is hailed by some as the first stage of the Reconquista.

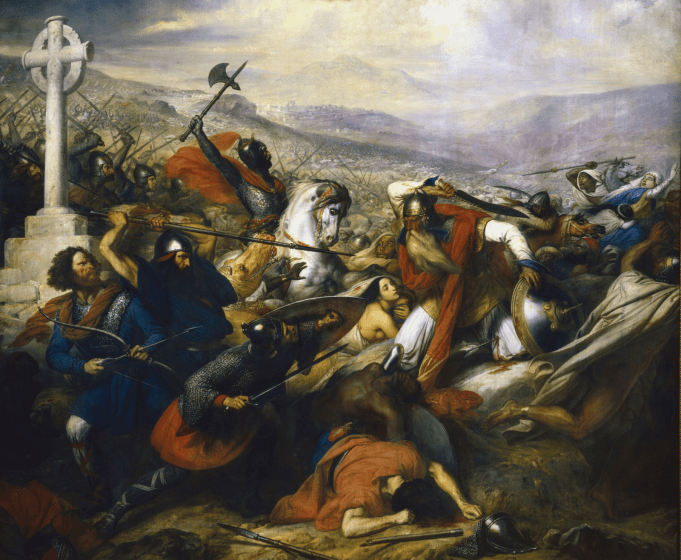

Battle of Tours/Poitiers — October 10, 732

This encounter took place near the border between the Frankish realm and the independent region of Aquitaine. Frankish and Burgundian forces — under Mayor of the Palace Charles Martel‘s command — fought against an Umayyad army led by al-Ghafiqi, the governor of Al-Andalus.

In the preceding decades, the Muslims had conquered Iberia. They were making tentative expeditions in southern France. They were pushing the limits of their expansion far from the regional capital of Córdoba. At the battle, Martel’s forces defeated Al-Ghafiqi’s contingent. It included about 70 Muslim families unprepared for warfare.

The battle’s location is described in Arabic historical works as “The Plain of the Martyrs.” Historians give little attention to the engagement itself as a minor skirmish. However, European chroniclers increasingly began to praise Charles Martel as the champion of Christianity.

What’s more, 18th and 19th century historians came to characterize this battle as a decisive turning point in the struggle against Islam. Modern historians are divided as to whether the victory should be considered a landmark event that saved Christianity and halted the conquest of Europe by the Muslims.

Battle of Roncesvalles — August 15, 778

Roncesvalles is situated in the Spanish region of Navarre, close to the French border in the Pyrenees Mountains. The army of the Frankish king, Charlemagne, had entered northern Spain. He hoped to extend his empire’s boundaries into Iberia, capturing Barcelona and Pamplona.

Frankish commander Roland and his troops — comprising the army’s rear guard — were returning to France across the Pyrenees. Suddenly, local Basque Christian tribes attacked Roland and his army unexpectedly. Though poorly equipped, these tribes knew their terrain well and defeated Roland’s forces at the Pass of Roncesvalles in 778.

The famous Song of Roland, dated about 1100, immortalizes his valor. It is the earliest existing French epic poem (chanson de geste). However, the poem relates that a Muslim army of 400,000 attacked Roland and the rear guard. Roland could not repeal the onslaught. His comrade urged him to summon aid from Charlemagne by sounding his horn, but it was too late. Handed down by oral tradition, this minor battle was romanticized into a major conflict between Christians and Muslims.

Battle of Zallaqa — October 23, 1086

On May 25, 1085, Alfonso VI of Castile took Toledo. He established direct personal control over the Muslim city from which he had been exacting tribute. This turn of events alarmed the rulers of other petty kingdoms. They began to realize their own disunity had strengthened Christian states in the north.

In order to counterhalt the Christian advance, the Muslims needed assistance from determined and capable warriors. Three of the petty kings, including al-Mu’tamid of Seville, decided to invite Almoravid leader Yusuf ibn Tashufin. He was the head of a new religious and political movement in North Africa. They agreed to have him come to Andalus and help them fight the Christians. Afterwards, they expected him to return to his capital at Marrakesh.

Ibn Tashfin agreed to help the Andalusians. He crossed over to Iberia with 7,000 warriors. He marched north to al-Zallaqa. There, the petty kings’ forces joined his troop. By then, the Muslim army reached 30,000 soldiers.

Alfonso VI of Castile arrived at the battleground with his large army. Using a variety of tactics, the Muslim forces were able to defeat the Christians. The casualties of Alfonso’s troops were tremendous: only 100 knights returned to Castile, including Alfonso himself.

Following the battle, Ibn Tashufin kept his word and returned to North Africa, only to be called back again to help hamper renewed threats. His return led to Andalus’ inclusion in the Amazigh (Berber) Almoravid Empire.

Battle of Alarcos — July 18, 1195

The Almohads were a Amazigh (Berber) religious and political reform group founded by Ibn Tumart. They came to power in North Africa in the mid-12th century.

Ibn Tumart’s disciple, Abd al-Mu’min, led the Almohads in conquering Marrakesh and overthrowing the Almoravids. In 1149, the Almohads replaced Almoravid rule in Al-Andalus.

King Alfonso VIII of Castile decided to attack the region of Seville. He had the support of the military Order of Calatrava. The attack ravaged the province, taking much war booty.

Almohad ruler Abu Yusuf Ya’qub al-Mansur crossed to Spain to lead a retaliatory expedition against the Christians. Local governors and a small Christian cavalry under Pedro Fernández de Castro, who opposed Alfonso, raised the troops that reinforced Al-Mansur.

The two sides met at Alarcos (al-Arak in Arabic), near the Guadiana River. Al-Mansur’s army severely outnumbered Alfonso’s troops. But, Alfonso entered battle rather than retreating and waiting for reinforcements. The Almohads were victorious, although there were significant casualties on both sides.

The battle’s outcome threatened the Kingdom of Castile’s stability for some time. The Christians abandoned or surrendered all nearby castles.

Abu Yusuf settled in Seville to consolidate Muslim holdings, rather than attempt conquests northward. He took the title of al-Mansur Billah (“Victorious by the Grace of God”). He initiated the construction of the Great Mosque of Seville, including the massive minaret (later known as the Giralda).

In 1198, he returned to North Africa. After Al-Mansur’s death in February 1199, the Almohad Empire began to falter. The empire’s decline opened the way for renewed Christian expansion into southern Spain.

Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa — July 16, 1212

Following their victory at Alarcos, the Almohads conquered such key cities as Trujillo, Plasencia, Talavera, Cuenca, and Uclés. They also took a stronghold of the Calatrava Knights.

The Almohad threat prompted Pope Innocent III to call for a crusade in Iberia. The Pope convinced King Alfonso VIII of Castile and his Christian rivals — Sancho VII of Navarre, Afonso II of Portugal, and Peter II of Aragon — to set aside any enmity and join forces against the Muslim south.

Almohad ruler Muhammad al-Nasir brought together troops from his extensive North African domains and Al-Andalus. They engaged the Christian coalition at Las Navas de Tolosa. The battle took place near a pass separating southern Spain from the central meseta.

Alfonso’s forces caught the Muslim army by surprise. The Muslims suffered a great many casualties. Al-Nasir escaped and returned to Marrakesh, where he died soon afterward.

The Muslim forces were unable to recover from this defeat, called al-Uqab in Arabic (“the great tragedy”). As a result, Andalusi cities such as Jaén, Córdoba , Seville, Jerez, and others were exposed to Christian attack in the mid-13th century.

Battle of the Rio Salado — October 30, 1340

King Alfonso XI of Castile and King Afonso IV of Portugal joined forces to resist the combined army of Nasrid ruler Yusuf I of Granada and Marinid ruler Abu al-Hasan Ali from North Africa.

The Granadan rulers allied with the Marinid Dynasty in Fes, because they were not strong enough on their own to engage the Christian states.

The Nasrid-Marinid alliance represented an effort to reclaim lost territories in southern Spain. There, substantial numbers of Muslims still lived as Mudejars in communities under Christian rule. But the Granadans were wary not to allow the Marinids too much influence in the shrinking territory of Al-Andalus.

The battle took place near the River Salado. There, the Christians decisively defeated the Marinids, who made up the bulk of the forces. The Marinids then returned to North Africa.

Subsequently, Alfonso XI’s son, Pedro of Castile, maintained cordial relations with the Nasrids of Granada. He admired their courtly culture so much that he called craftsman from Granada to upgrade the Alcázar of Seville in the style of the Alhambra palace.

Conquest of Granada — January 2, 1492

Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon married in 1469. Their marriage instituted a policy of extending the Catholic faith throughout the peninsula.

The Kingdom of Granada remained as the sole Muslim domain in Spain. Yet, it no longer thrived as it once did. Thus, it was less probable to offer tribute to the Christians in lieu of conquest.

The Catholic Monarchs amassed their armies on the plains west of Granada at a place they named Santa Fe. The Granadans contemplated a course of action. The elders of Granada signed a treaty of surrender, with a promise from the Christians to be granted freedom of religion and personal safety.

The twenty-third and final Nasrid ruler, Abu Abd Allah (Boabdil), delivered the city into the hands of Ferdinand and Isabella to end the city’s siege. The Catholic Monarchs hoisted their banner from atop the Alhambra’s citadel, proclaiming their victory.

It is often depicted that Boabdil and his entourage headed into exile, glancing wistfully back upon the once shining city that his dynasty had ruled for 250 years. However, Boabdil accepted his new status as King of the Alpujjaras. About a year later, he decided to abandon his people and go into exile.

Revolt of the Alpujarras — 1568 to 1571

The policies of Cardinal Jimenez de Cisneros increasingly pressured Granada‘s Muslim population — initially Mudejars — to convert to Christianity. As new Christians, they were called Moriscos (or “Moroccan-like”).

The Hapsburg ruler of Spain, Philip II (son of Charles V), introduced laws prohibiting the practice of Muslim religion and customs to accelerate conversion. However, many Moriscos continued to practice Islam in secret. They began organizing opposition to the restrictive policies.

In 1568, the Moriscos rallied under the leadership of Ibn Humeya. They initiated a guerrilla war against Spanish authorities. This uprising took place in the Alpujarra Mountains south of Granada. Castilian troops — led by Philip’s half-brother Don Juan de Austria — suppressed the revolt, ending it in 1571.

Conflicts between Moriscos and Christians continued. As a result, in 1609, Philip III issued a decree of expulsion of the Moriscos. Similarly, in 1492, the Catholic monarchs’ decree of expulsion forced the Jews to seek a more tolerant environment.