What’s For Breakfast?

Explore how items used in daily life originated in Medieval Spain under Muslim rule.

Centers of Learning

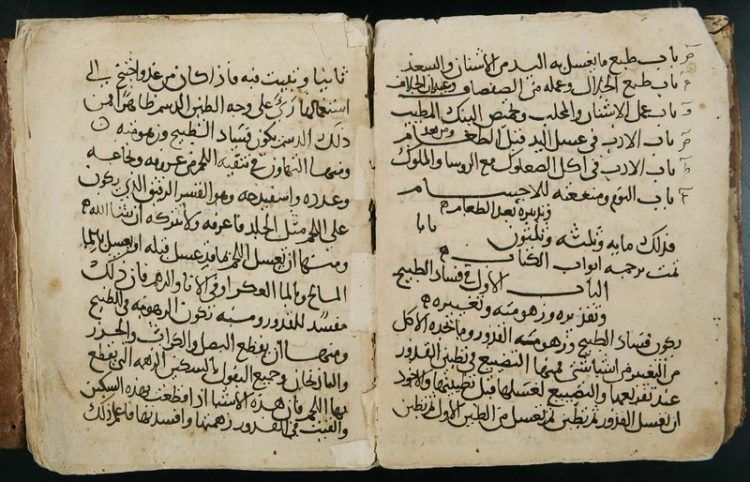

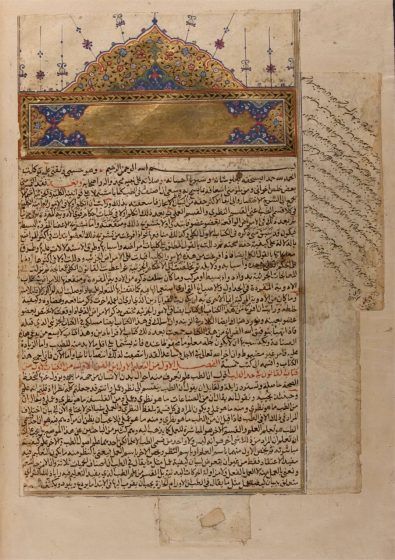

The development of the science and culture of Islamic Spain began with the spread of Islam which in turn spread the Arabic language across Afro-Eurasian lands, from Central Asia to the Atlantic. As more people began using Arabic, people communicated with greater ease, which allowed more people to produce books and other pieces of writing.

Muslim governments established centers of learning to collect these works, just as the Greeks, Romans, and Persians had done under their rule. In these centers, they would also translate scientific, literary, and philosophical works.

Among the most famous centers of these translations efforts was the House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikma in Arabic). Caliph al-Ma’mun established this center in 870 C.E. in Baghdad.

Al-Hunayn, a Christian scholar, led a great effort to collect and translate available knowledge. Countries sent emissaries to purchase books from wherever they could be found.

Invention of Paper

Around the time the House of Wisdom was founded, a new technology helped to advance the spread of knowledge: paper-making.

In the early 700s, the Chinese invention of paper arrived in the Muslim countries of Southwest Asia. Suddenly, making books became cheaper and easier. While parchment was a good writing material, it was made from expensive animal skins. Papyrus was cheap, but not very durable. In comparison, paper could be made from cotton, linen, and other plant fibers, or even from old rags.

In the growing cities of Muslim lands, people bought, wrote, and collected books more than they had ever before. Instead of having just a few copies of an existing work, more could be produced much more easily. This increased production improved chances that the work would not be lost to history.

Books and paper-making spread westward across Africa to Al-Andalus, along with the use of water power to pound fiber. The result: libraries in Muslim lands grew to thousands of volumes — even though books were still copied by hand!

Learn more about the spread of paper from China to Europe here.

Growth of Knowledge

Muslims, Jews, and Christians took part in the growth of learning and culture in eastern and western Muslim lands.

The cities in western Muslim lands — including Córdoba, Toledo, Seville and Granada — shared in this book and scholarship exchange. Scholars in different places using the same book corresponded with each other. They shared thoughts and ideas. Their efforts allowed for the growth of knowledge between cities, and the spread of science and culture from Islamic Spain to other regions of the world.

There also were other key factors advancing knowledge growth. Trade, travel, and migration sped up this process. Increased wealth also fueled this knowledge growth. The use of Arabic language and Islamic law spread with the accumulated knowledge.

It was indeed a very dynamic period of learning. The House of Wisdom became a translation center, library, museum, and institute for scholars. There, scholars copied, studied, and discussed books from every angle.

What’s more, Baghdad’s scholars worked with scientific ideas everywhere — in courts, palaces, streets, homes, and bookshops. They tested them by measuring, experimenting, and traveling. In time, they developed a large body of new knowledge, adding to the wisdom of ancient times.

Faith and Knowledge Growth

One important concern — which would be shared across religious boundaries — was the question of how these ancient ideas fit in with Islamic teachings. If scriptures were a revelation from God and contained all wisdom, as they believed, was it permitted to look to other sources of knowledge?

Numerous scholars wrestled with this issue. But they generally reached agreement that faith or belief and reason or independent investigation are not just permitted, but encouraged. God created human beings with the capacity to think and reason. Like other human abilities, it could be used for good or for evil.

This important balance between faith and reason would be explored for centuries. It would be passed on through the work of Muslim, Jewish, and later Christian philosophers and scientists.

This shared understanding among the Abrahamic faiths put into place one of the cornerstones of modern science. And, the scholars of Al-Andalus played an important role in its formation and transmission.

Institutionalized Learning Grows

Educational institutions such as schools, universities, and libraries spread across the network of Muslim cities. Mosques offered classes in reading Arabic. Meanwhile, the wealthy employed tutors in their homes or palaces.

From the 800s to the 1100s, major Muslim cities established formal schools and colleges. There were also several important pre-Islamic Spain universities used for teaching and research.

For example, there was a college in Cordoba attached to the Umayyad caliphate. In Baghdad, the Seljuk Turks established the Mustansiriyah, a renowned university, and at the same time the Fatimid rulers in Egypt founded Cairo’s famous al-Azhar University.

Traveling students — including young European scholars — came to these colleges to learn Arabic and become educated in knowledge collected in libraries. They also transmitted important ideas and styles of song, poetry, and new foods once they returned home.

Muslim-ruled territories in Spain and Sicily became centers of Muslim learning and culture. These Mediterranean lands within Europe served as links to the East.

Contact between Christians and Muslims during times of both war and peace helped develop Christian Europe’s culture by luxury goods, music, and fashion acquired through al-Andalus. Curious scholars — including Church officials — traveled to Al-Andalus to learn about these things firsthand. They wanted to see the libraries filled with books in Arabic on many important and useful subjects.

Groups of Jewish, Christian, and Muslim scholars sat down together to translate these works from Arabic to Latin, with the support of certain Christian rulers. This translation effort mirrored the one at the House of Wisdom in centuries earlier.

Practical Uses of Knowledge

During the 1100 and 1200s, Latin translations of Arabic books fostered changes in Europe’s schools and growing cities. Books about mathematics — including algebra, geometry and advanced arithmetic — introduced Arabic numerals. Yet, it took another 200 years before Arabic replaced Roman numerals in Europeans’ everyday life.

North African and Italian merchants’ use of Arabic numerals enabled them to spread among merchants, who also did their own bookkeeping, or accounting. Meanwhile, other books brought knowledge about astronomy — contributions from Greek, Persian, and Arabic sources.

Geography, maps, and navigational instruments allowed Europeans to see the world in a new way. These navigational instruments included the astrolabe, the quadrant, the compass, and the use of longitude and latitude to create accurate maps and charts.

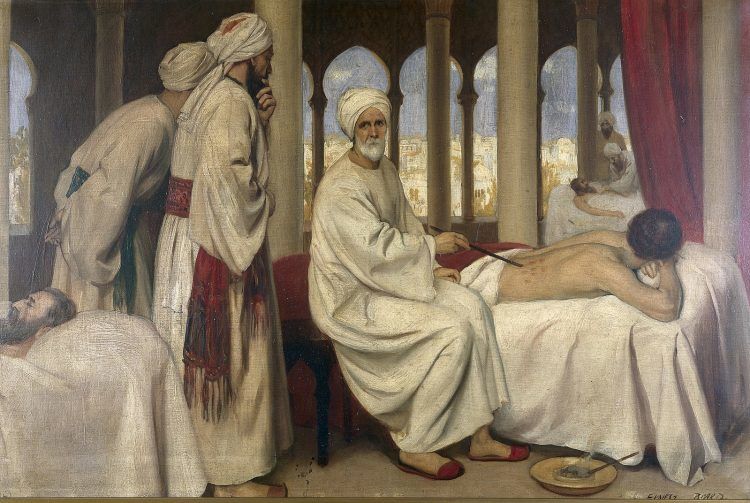

Medical books — especially by Ibn Sina, al-Razi, and al-Zahrawi — and some classical Greek works, lifted the cloud of superstition over illness. What’s more, descriptions of diseases and cures, surgery, and pharmacy — the art of preparing medicines — helped develop a medical profession in Europe. More than anything else, the spread of medical texts spread the science and culture of Islamic Spain.

Modern writers Francis and Joseph Gies summarize the importance of translation work taking place in Spain after the Christian conquest of Toledo in 1085:

It was the Muslim-Assisted translation of Aristotle followed by Galen, Euclid, Ptolemy, and other Greek authorities and their integration into the university curriculum that created what historians have called “the scientific Renaissance of the12th century.” Certainly the completion of the double, sometimes triple translation (Greek into Arabic, Arabic into Latin, often with an intermediate Castilian Spanish … ) is one of the most fruitful scholarly enterprises ever undertaken. Two chief sources of translation were Spain and Sicily, regions where Arab, European, and Jewish scholars freely mingled. In Spain the main center was Toledo, where Archbishop Raymond established a college specifically for making Arab knowledge available to Europe. Scholars flocked thither … By 1200 “virtually the entire scientific corpus of Aristotle” was available in Latin, along with works by other Greek and Arab authors on medicine, optics, catoptrics (mirror theory), geometry, astronomy, astrology, zoology, psychology, and mechanics.