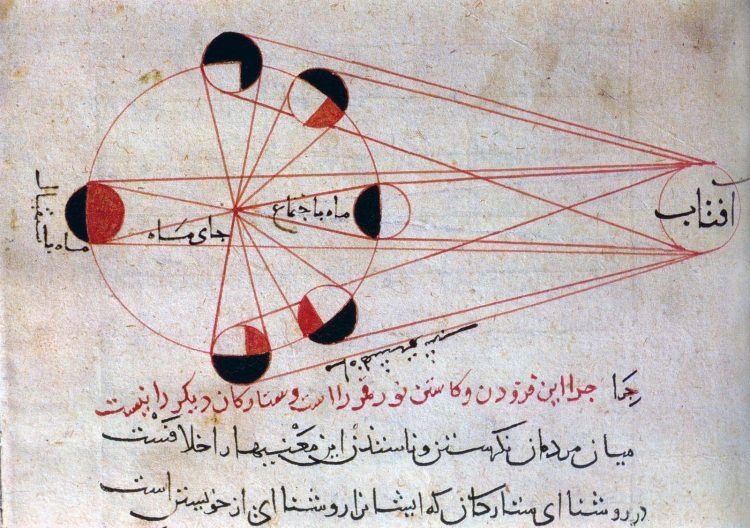

Astronomy may not seem so essential today, but that is only because we take accurate calendars and clocks for granted. We scarcely notice the phases of the moon, the sun’s passage marked by equinoxes (fall and spring dates of equal daytime and nighttime) and solstices (longest and shortest days of summer and winter), because they no longer seem essential to our lives. To get from one place to another, we use interstate highways and road maps, not devices for navigating by the stars.

In contrast to us, Medieval societies made great efforts to establish accurate calendars for celebration of religious holidays and for plowing, planting, and harvesting. Astronomy was necessary for these practical reasons. Scientists who gathered this knowledge were also curious to know more about the celestial bodies that fill the sky at night, and to understand their relationship to the sun, the moon, and the earth.

Al-Andalus was open to knowledge from eastern Muslim lands, where knowledge from many cultures and religious groups was gathered together during the 800s CE. Early Muslims absorbed Indian, Mesopotamian, Persian, Greek, and Roman knowledge of astronomy.

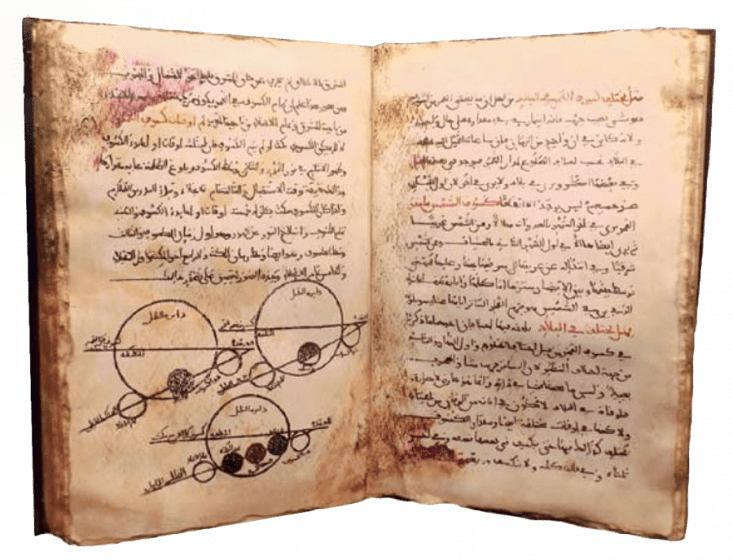

Among earlier works that played a large role was a system of astronomy associated with Ptolemy, a mathematician who lived around 150 CE in Alexandria, Egypt. His system was widely believed, but as observations continued, astronomers found that it couldn’t explain the movement of the planets and the sun that astronomers observed, since it placed the earth at the center of the universe.

During the next 1500 years, astronomers continued their observations and developed mathematical and mechanical models to explain this observed movement. Astronomers working in Muslim lands some Muslim, some Jewish and some Christian –wrote books with diagrams and formulas, trying to improve on Ptolemy’s system.

Among the earliest Muslim astronomers was al-Faraghani (fl. 863 CE), who summarized but questioned Ptolemy’s work and made many important calculations. Columbus used his figures on the earth’s circumference, but misunderstood the astronomer’s unit of measurement. Al-Khwarizmi (ca. 770-840 CE), the famous Persian mathematician, prepared astronomical charts that were later translated and further developed in Spain.

Al-Battani (d. 929 CE), another critic of Ptolemy, contributed to solving the puzzle of the heavens, and whose work was used for centuries. He calculated astronomical tables (charts on the movement of bodies in the sky), and helped to develop the branch of mathematics called trigonometry, which he used to calculate accurate solar and lunar timekeeping.

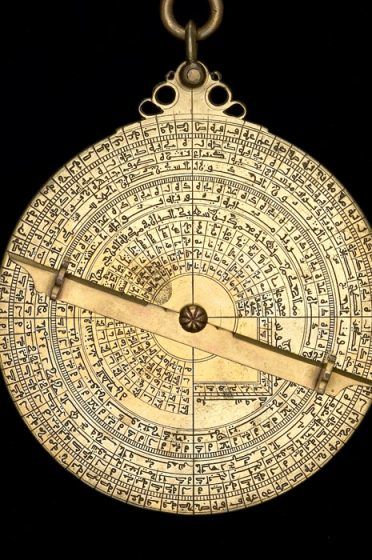

Astronomy in Spain built on the work being done in the east. In Córdoba, Spain, al-Zarqali (1029-1087 CE) prepared astronomical charts called the Toledan Tables. He also built and improved on the astrolabe, a tool with hundreds of uses in astronomy, navigation, surveying and timekeeping.

Jaber ibn Aflah (d. 1145 CE) is considered important for his advancements in trigonometry. Using spherical trigonometry, he designed a portable celestial sphere. Al-Bitruji (d. 1204 CE) was a leading astronomer who was born in Morocco and migrated to Seville, where he developed a new theory of the movement of stars.

Translation of books on mathematics and astronomy in Spain from Arabic through Hebrew and Castilian into Latin added to the contributions of Al-Andalus to advancing astronomy in Europe. Historians of science have long known about these translations, where they were published, and which scientists owned these books. Recently, it has become known that some European scientists had direct or indirect knowledge of Arabic, and we are learning that there was more than one path by which learning was exchanged between East and West.