Manufacturing and Agriculture

Before the Muslim conquest of Spain, Romans created an extensive infrastructure of roads, bridges, aqueducts, and urban centers in various parts of Iberia.

They also grew crops such as cereal grains, olives, and grapes on large estates in the region. These crops were harvested and exported to other regions of the vast Roman Empire. Spain quickly acquired a reputation for plentiful harvests and rich natural resources.

The Muslim conquest of Iberia prompted the introduction of new agricultural technology, innovative irrigation practices, and many new crops to Al-Andalus. This dramatic agricultural transformation was known as “The Green Revolution.”

The Andalusi people took their cues from such eastern lands as Dar al-Islam (meaning “Abode of Islam”), which saw itself as part of a huge trading network that extended across the Mediterranean, the Indian Ocean and the Silk Route.

Andalusi historian al-Himyari — illustrating this sense of connection to the East and the Andalusi people’s mixed cultural preferences — likened Al-Andalus to Syria in fertility, Yemen for its moderate climate, India for its aromatic plants, China for its mineral richness, and Aden for its seashore economy.

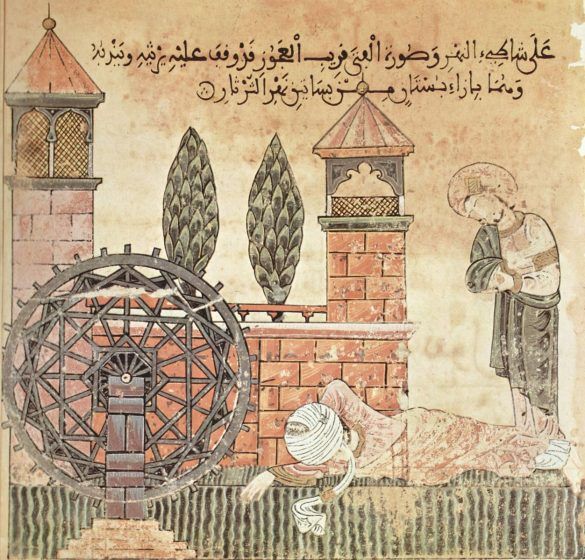

Arab Muslims effectively “Syrianized” the landscape of Southern Iberia through wide-scale use of the noria(waterwheel), the qanat (underground water channel) the aljibe (cistern), and other structures from the east.

The use of precise water management techniques, coupled with multi-seasonal planting and harvesting, increased agricultural output. Rulers and merchants alike sponsored the introduction of a vast new array of crops that originated in such countries as China, India, and Persia. The Andalusi people enjoyed many foods previously unknown in Iberia, including sugarcane, citrus, melons, figs, spinach, eggplant, and rice.

These innovations increased the amount of water available for irrigation throughout the year and overcame the limits of previously used gravity-fed irrigation. During the height of Umayyad rule, historic sources indicate over 5,000 waterwheels were built along the Guadalquivir River alone (Arabic: Wadi al-Kabir, or Great Valley).

At the same time, cotton and mulberry trees for silk worms were introduced. Learned botanists, such as Ibn Bassal and Ibn al-Awwam, would first acclimatize new plants in royal gardens.

This agricultural explosion served as a foundation for an expanding population and greater prosperity throughout Al-Andalus.

Historians agree that this agricultural explosion served as a foundation for an expanding population and greater prosperity throughout Al-Andalus. Arabs acquired newfound wealth in Andalusi cities. The formation of this new elite further stimulated acculturation to Arab-Muslim norms.

Soon, the masses at large were emulating the elites’ lifestyle and cultural preferences, including culinary habits, intellectual and artistic expression, and leisure pursuits such as chess and backgammon. They desired clothing, jewelry, and material objects communicating an upwardly mobile status and refined taste.

This shift further stimulated the Andalusi economy and its integration with trade networks. Artisans worked in caliphal workshops at Madinat al-Zahra to produce marvelous fabrics, ceramics, and trinkets. Craftsmen produced unique luxury objects, including intricately carved ivory caskets, which depicted hunting scenes and other imagery associated with rulership. The caliph and other Umayyad elites often presented these ivory boxes to friends and loyal servants, such as to Córdoba’s chief of police.

The caliphal workshops produced silken robes, called tiraz, and clothing that represented the fashionable brand of the day. These workshops also created ceramics with particular green and black paint associated with the caliphal household — the White House Chinaware of the time.

Each of Spain’s major cities came to be known for the crafts in which their artisans specialized. In fact, people from around the world still revere many of these crafts today.

For example, Seville became known for assembling quality musical instruments. Córdoba became famous for its leather goods, a reputation still maintained today.

Meanwhile, Toledo served as the center for luxury metalwork and arms. Craftsmen designed swords using a special grade of steel and forged through a secret process providing extra strength and sharpness. Today, tourists in Toledo can also find numerous shops offering damasquinados, which are black and gold jewelry and objects made in Damascus-style geometric patterns inherited from Islamic times. Visitors to the Alhambra in Granada are awe-struck by its architectural beauty. But, even more remarkable is remembering that when it was lived in, this and other palaces like it in Al-Andalus were not the bare structures they are today.

Today, visitors admire the Alhambra in Granada for its architectural beauty. Equally remarkable is that this and other palaces in Al-Andalus were once lavishly decorated. Rugs adorned the floors; colorful draperies and azulejos (interlocking geometric tiles) covered the walls; and wooden beds, sofas, and chairs with cushions provided comfort. There were brightly painted alcoves and ceilings, creating a kaleidoscope of color.

Gardens and fountains added texture and visual splendor, both indoor and outdoors. Aromatic plants and flowers were planted in strategic locations to provide fragrant scents. And the sound of trickling, bubbling water in fountains abounded everywhere. Open doorways and windows helped unify interior space with the surrounding environment.

All these practices were visible at varying degrees in all levels of Andalusi society. Consequently, Al-Andalus acquired a reputation for sumptuous living.

Watch a movie about development in Islamic Spain here.