Transfer of Knowledge

Learning Evolves In Europe

In the 1100s, there was a new desire for learning that developed in Europe, especially in the towns.

Farming was improving. Trade began to grow. So, towns along trade routes also expanded.

Growing towns needed skilled artisans and merchants, and stronger governments. They needed systems of law and people to keep records. Schools began to educate the sons of wealthy merchants in more worldly subjects; church learning was not enough. With the entry of newly translated books from Spain and Italy, the quality of learning was gradually advancing.

Philosophy Meets Faith

Philosophy means “love of wisdom” in Greek. Aristotle, Plato, and other famous Greek philosophers wrote and taught about reason, moral teachings, and human behavior.

Jews, Christians, and Muslims share the important set of ideas set forth by Greek thinking. Philosophers of all three faiths have discussed how Greek ideas could be melded with the teachings of their scriptures.

They have written about the links between God-given reason and God-given revelation and faith. People have spent their entire lifetimes thinking, writing, and teaching about such philosophical questions as how humans can balance the urge to question with the necessity to believe.

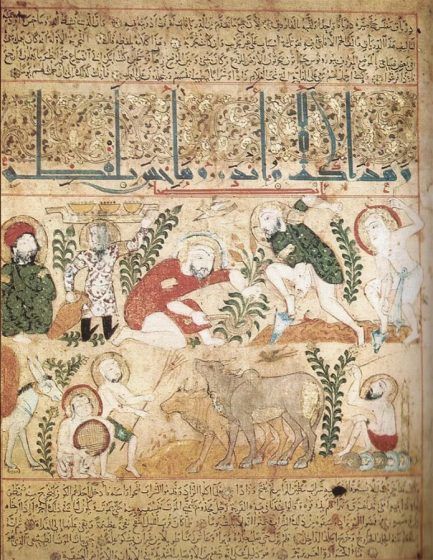

If the House of Wisdom had not been preserved in Arabic classical works of Greek and other ancient philosophers and scientists, they may have been lost to Europeans. Muslims translated the works, wrote comments and explanations, and added their own ideas.

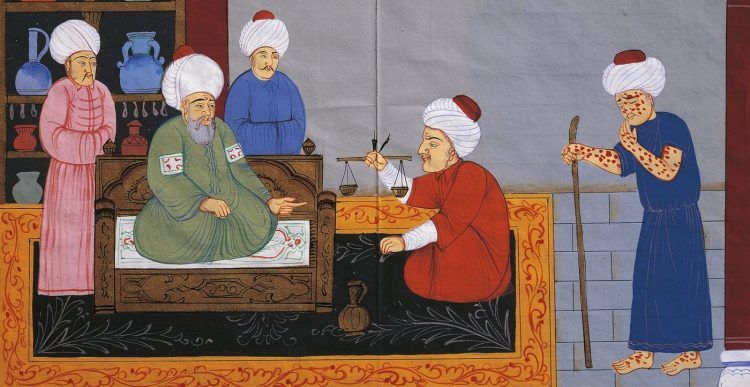

The Spanish Muslim, Ibn Rushd, and the Jewish thinker, Maimonides, commented on Aristotle. They both were born and worked in Islamic Spain. Other Muslim philosophers — such as al-Kindi, Ibn Sina (Avecinna, the medical writer), and al-Ghazzali — had also written about faith and reason. Their works were translated into Latin. They stimulated Christian scholars to discuss reason and faith.

The similarity of thought and ideas of Islam and Judaism with Christianity gave way to meaningful translations and commentaries from such great thinkers as Thomas Aquinas. Aquinas was a scholar of the 12th century. He wrote a famous work on this subject, called the Summa Theologica. It contains ideas from Greek and Arab/Muslim thinkers. Europeans and Muslims alike were attracted to Aristotle and Plato’s ideas.

Most importantly, the work of philosophers — whether Greek, Muslim, Jewish, or Christian — offered solutions, which opened the way to scientific thought. They made it acceptable to investigate the natural world, draw conclusions about it, and attempt to discover the laws of nature.

Learning Transforms Higher Education

The entry of new learning into Europe had a huge effect on higher education. Students and scholars wanted to study these important new works. So, they eagerly sought out teachers who had read them.

Europe developed colleges as centers for teaching and research in medicine, law, mathematics, astronomy, and physics. Universities in Paris, France, and Oxford and Cambridge, England, were founded. A college at Bologna specialized in law. Another at Salerno taught new medical knowledge discovered by Arab doctors.

Changes in knowledge opened up new ways of thinking among educated Europeans. Volumes of ancient wisdom, new learning, and literature filled libraries. This historic period is known as the Renaissance, or “rebirth.”

Learning and the Renaissance

The discovery of classical and Arabic learning set off the search for works “lost” after the fall of Rome. During the Renaissance, European scholars re-explored these works and brought a fresh perspective on the past. They put aside the rigid, narrow thinking of the Middle Ages. They found ways to build a better life and future, using these ideas.

A group of philosophers, called humanists, improved the teaching of Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and even Arabic. Their discovery of Greek and Latin writings led them to travel, discuss, and debate.

Despite changes taking place in universities, new knowledge reached only the tiny group of Europeans who attended college. However, Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press in 1450 set off an explosion of literature and learning.

Together with paper-making technology — which entered Europe through Islamic Spain — book production became much easier and cheaper. Books became trade goods sold on expanding trade routes all over Europe.

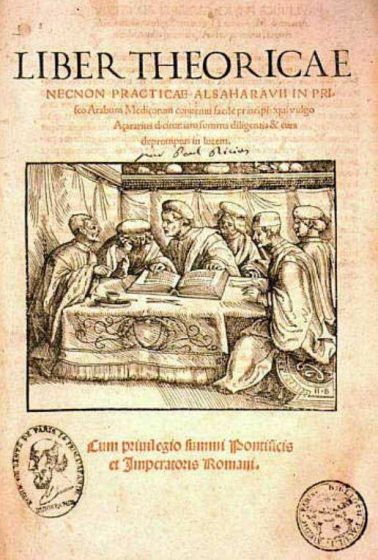

Wealthy customers — often merchants and aristocrats — bought scientific books to add to their libraries. Scientific books — translated from Arabic two centuries earlier in Spain — now became available in print.

Authors with Latinized Arabic names appeared in newly printed books on such subjects as medicine, astronomy, agriculture, metallurgy, and meteorology. They included Avicenna (Ibn Sina), Geber (Jaber), Averroes (Ibn Rushd), and many others.

Most of the works, which influenced teaching at European universities in the 1200s, now had an even greater impact. During the next 300 years, some of these books continued to be printed and re-printed.

New Age of Discovery

The work of these Muslim, Jewish, and Christian scholars centuries earlier sparked a new age of discovery in Europe.

The Scientific Revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries resulted from the transfer of knowledge five centuries before. Developments in scholarship and education leading to the Renaissance also played an important role. And, in turn, the Renaissance and Scientific Revolution brought about the Industrial Revolution.

It took more than a few people in one part of the world to bring about the changes leading to the Renaissance and Scientific Revolution. History proves that exchanges among many cultures over a very long period of time contributed to modern inventions and scientific understanding. Ultimately, it is the result of humanity’s desire and cooperation to preserve and pass on knowledge from one generation to the next.

Learn more about the journey of knowledge into Spain here.